At Thomas Coram Nursery school, we have been working for a long time with children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or those with traits consistent with autism. In the past few years we have felt that the number of these children has noticeably increased. The pandemic had left some of the families of these children more isolated than ever before. We wanted to do more for them and their children, and this made us think about our whole approach to inclusion.

As a maintained nursery school with around 150 children on roll, we are fortunate to have large outdoor spaces and open-plan classrooms. For most of the day, children move freely indoors and out. For some children with ASD, this level of free choice works well, but for others, a busy, noisy and highly social environment can feel overwhelming and difficult to manage. We have been developing our curriculum for children with ASD over the years, but realised there were some problems with our approach.

Our overall aim is for all children to access the full nursery curriculum independently, including engaging with all the activities and making free choices in play. However, for some children with ASD, we may need to directly teach play skills and how to use materials. We also support children to play alongside and ideally with other children. Alongside this we offer some particular specialist interventions, some of which are outlined below.

INTERVENTIONS– THE THEORY

Transition objects (‘objects of reference’)

One of the first strategies we introduce to children who are having difficulty with communication, this is designed to help children understand what is about to happen. We use an object consistently to indicate routines such as nappy change or using the toilet, snack time, etc. We also use consistent phrases like ‘lunch time’ to help children understand routine events which we couple with an object (giving a particular plate), before encouraging them to move to the lunch area. We always give the child ‘processing time’ before we try to start the routine. The objects have a symbol attached linked to the routine – this is so that later on, the child can use a visual timetable or just a symbol card without the need for the object.

This strategy can have a huge impact on children who are finding it hard to understand what is being said to them. Many children learn to simply move in the direction of the activity when they hear the phrase and are given the transition object. This is often a key factor in reducing tantrums and resistance to routines. Of course, as with all children, there are times when the child doesn’t want to comply or when other factors are distracting them from the instruction, but at least they have a chance of understanding what is happening. By the time they go to school, some children are ready to move to symbols only alongside the key phrases.

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)

This approach to communication was developed in the US in the 1980s by Lori Frost and Andy Bondy. The child is taught to exchange a picture card for something that they want, commonly a food item or favourite toy. The child gradually learns to ‘request’ using the picture cards from a range of adults (and potentially children) in a variety of contexts, including in free play in the nursery.

Some of our children will still be pre-verbal when they transfer to Reception, but they are usually able to use PECS to request things and we liaise with their new school to explain how they use PECS. Some will take their PECS communication book with them and also use it at home. This gives them a chance to ask for things from day one at school. Some children start using PECS but then develop speech and start using words as well as the picture cards to request.

Workstation (from the TEACCH Approach)

This gives children with autism a chance to develop independent skills and also feel a sense of mastery and achievement. It involves setting up a table and chair in a relatively quiet area. The child then has regular sessions in which they gradually learn to take a task from the ‘start tray’, complete it and put the finished task in the ‘finish tray’. The tasks will be short activities that the child enjoys and is already able to do, for example completing a small inset puzzle or posting shapes in a sorter.

Many of our children will get to primary school age able to complete six or more tasks at time independently at their workstation. Their enjoyment and growing competence with it allows us to include tasks which also help them develop skills that they might avoid in other contexts; for example, including a mark-making task for a child who generally avoids drawing activities in the nursery.

Attention groups

We offer a daily group based on the Gina Davies’ Attention Autism approach, with around four to five children, supported by adults and led by a practitioner. ‘Bucket time’ as we call it was conceived to have four stages, the first being when the leader shows children interesting items from their ‘bucket’ of toys. When children are able to manage sitting and attending to this, we add the next phase until they are sitting and participating for around 15-20 minutes.

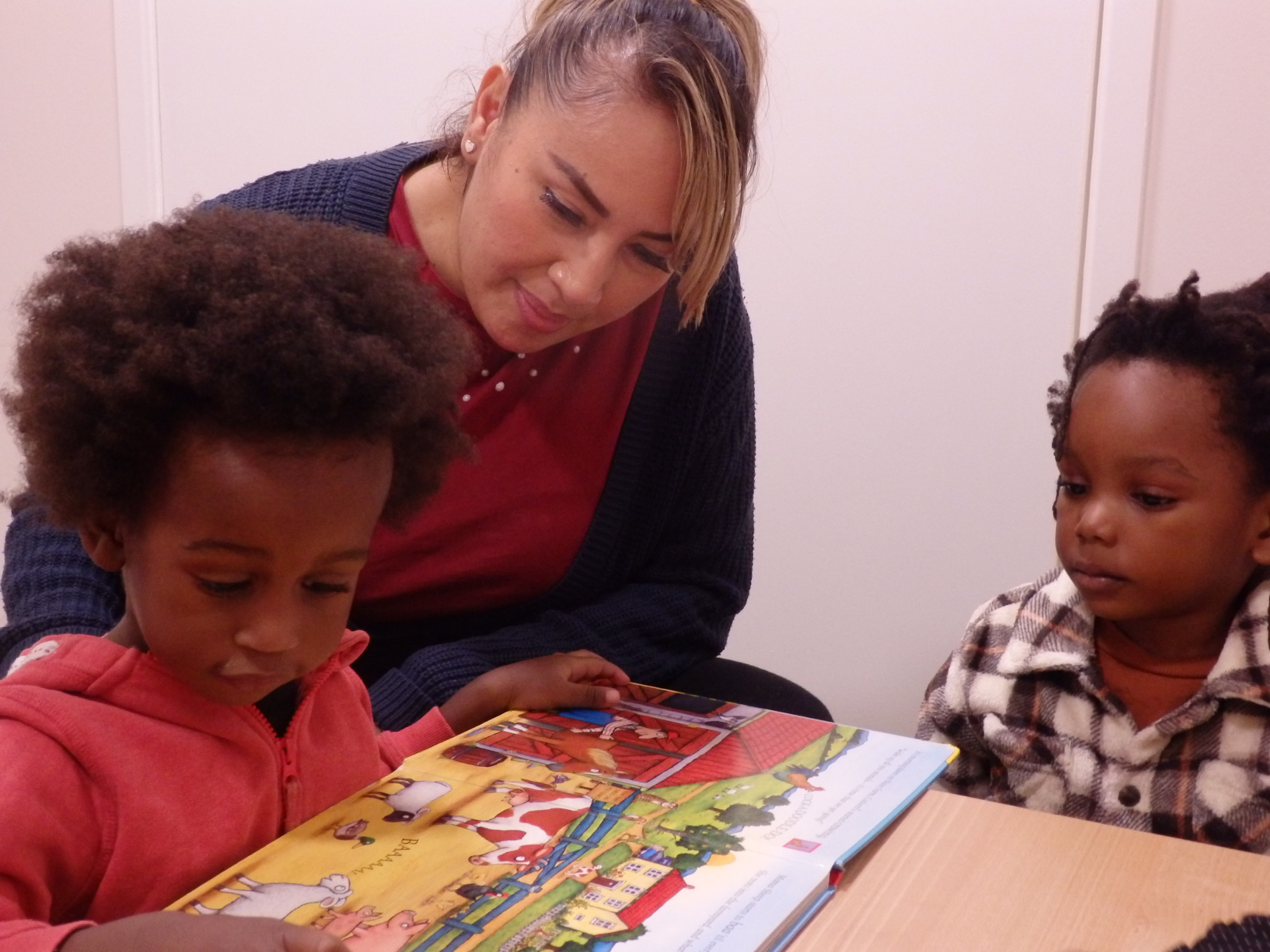

We also offer a small group with a set of four to five very structured activities lasting around 15 minutes called ‘special time’, which is based on the training from the speech and language therapists we work with. An activity is introduced with a visual prompt and consistent short phrase; for example, the leader might say ‘hello’ and lead a hello song or ritual, then say ‘hello is finished’ and the visual prompt for hello is posted by one of the children into a post box. The next activity might be taking turns to run a car down a track or blow bubbles. These include a lot of opportunities for children to take turns and hear a lot of repetitive language.

It usually takes some time for children to be able to sit and attend to a full group session. By the time children go to school, however, most are able to attend for most of a group and participate in activities to some degree, which can help a lot with skills such as shared attention, turn-taking, following an instruction, waiting, and a range of other skills, such as being able to share a book.

THE REALITY

Some of the interventions we use, such as using transition objects, can work really well, as long as all staff are sufficiently trained and have the resources easily available, but others, such as PECS, are designed to be taught in a very controlled environment. Children with ASD often have a heightened or different sensory experience to neuro-typical children and so are likely to be distracted by things that most of us are able to ‘tune out’; for example, pictures on the wall or the sounds of playing and talking. PECS needs to be delivered in a particular and consistent way, so staff also need to completely focus on delivery without too many distractions.

Because of this, it made sense to withdraw the children out of the nursery space for teaching sessions in a separate room, usually alone with their support worker. This meant that some children with ASD had a schedule out of the main nursery environment that took up most of their day, almost as if they were attending a separate school. Taking them out of the main nursery spaces meant they had much less opportunity to play freely or to make choices about the things they wanted to do. It also meant they had little opportunity to form relationships and make friends. Surely social experience was something that children with ASD desperately needed? It also reduced the opportunities for neuro-typical children to learn about difference and diversity. We knew this wasn’t the way we wanted to do things.

Then there was the problem that the majority of staff weren’t getting to know the children with ASD as well as other children, sometimes even if they were in their key group. Meanwhile, the children themselves were becoming overly dependent on their support workers. There has been significant research on why what is sometimes referred to as ‘Velcro-ing’ children to a support worker can stop them developing independence and negatively affect their outcomes (see further information). It also meant that many of the staff at the nursery knew little about interventions such as PECs or attention groups as they never saw them taking place.

Our dilemma about what works best for children with SEND reflects the wider debate in education and society about how we see people with additional needs. Should they be educated separately or included in mainstream schools like ours? Maybe we all need to learn more about the needs of our friends and neighbours so that everyone can fully contribute to society?

CHANGES WE MADE

Training and support for all staff

We made the decision to try to train all our staff at least in the basics of the interventions we were offering this particular group of children. This was to increase their understanding and also their confidence in interacting and supporting children with ASD throughout the nursery day. It was a big commitment that has taken us more than an academic year, but it felt key to shifting the isolation of the child with their support worker. All practitioners who work with children were given training in the early phases of PECS, in the use of transition objects and in how the small groups work. We encourage key persons and support workers to work as a pair in delivering the child’s individual education plan and the full curriculum. Training isn’t something that can be done once, so we have to commit to revisiting and reviewing all aspects of the work on a rolling basis, which is challenging but has started to pay off.

Moving the interventions back into the classroom (indoors and out)

Alongside the training programme for staff, we have experimented with ways to bring the specialist interventions back into the main nursery environment. We started by moving the teaching of PECS to the nursery classroom spaces. This threw up a lot of challenges and it may be that some children progress slightly slower than they might have done if they were removed to an empty space. However, the payoff is that children are now much more likely to start using PECS in the nursery, which is of course where they need to be able to communicate.

More children have been able to actively use PECs to request toys or activities and progress to having a communication book in the classroom alongside all the other children. Some practitioners have started to experiment with teaching children without ASD to be communication partners to their friends using PECS. We do make a compromise for children with a particularly high level of need who find it impossible to focus when there are distractions; in this case, we start in an adjacent space and gradually move the teaching into the main nursery. Now that all the practitioners are familiar with PECS, it also gives children a much greater chance of communicating with a range of people, not just their support workers.

We still have a long way to go, and the PECS system wasn’t designed to work with such a large free-flow space as ours, but we are gradually making progress. Many families also use PECS once children have learned the basics, which can really improve life at home. We have plans to integrate PECS further and keep trying new things.

Withdrawing to groups in a different way

We still wanted the children to access small group times (Special Time and Bucket Time )away from the hubbub of the nursery, but we realised that all nursery children go to one or two language-focused ‘story times’ or key group times daily (depending on their length of day). We rescheduled the groups for children with ASD to coincide with these, so everyone stopped playing and went to a group at the same time. This felt much more inclusive and meant that the children with ASD weren’t losing so much time to access the nursery activities.

Having more uninterrupted time in the nursery has meant that we are starting to see more relationships between children with ASD and their peers. Often this starts with something simple such as chasing games or giving another child a ride on your bike, but this kind of interaction and having a ‘friend’, even briefly, can make a huge difference in the life of a child with ASD. Just because we often see these children playing and exploring alone doesn’t mean this is what they want; they may just lack the skills to join other children in play.

What’s next?

We have started a support group for parents so that they can share experiences and ideas, which we are working to develop further. We have plans to find more ways to integrate the children with ASD and all the children and we hope to see more relationships forming as well as developing understanding from neuro-typical children.

We want to expand the ways children use PECS in play and for spontaneous communication as well as in teaching lessons, and overall we want to do more to share children’s achievements with their parents and carers.

We haven’t always been very confident, for example in videoing our work, but this is something we want to expand this year so we can share with families in the same way the SEND support team made their work more visible to key persons.

Jan Stillaway is deputy head teacher and SENDCo at Thomas Coram Nursery School and Centre

FURTHER INFORMATION

- PECS: https://bit.ly/3VhdDeW

- ‘Velcro’ support workers: https://bit.ly/3fVAbll

- TEACCH approach: https://bit.ly/3SUaxw2