A new report into the health of under-fives over the past two decades finds that inequalities between disadvantaged and advantaged children are increasing.

Meanwhile, separate research suggests the pandemic has created a widening inequality gap between children living in the North and South of England (see box).

Evidence review: Trends in early childhood health in the UK, published by the Nuffield Foundation, concludes that while young children are healthier than they were 20 years ago, progress on improving the health of under-fives has ‘stalled’ and there is now a ‘reversal’ of some of the long-term improvements.

According to the research, vaccination uptake and breastfeeding rates have increased; however, tooth decay is more prevalent in children and the pandemic has led to a ‘spike’ in rates of childhood obesity, worsening parental and child mental health and reduced services.

It finds poverty is a ‘significant’ driver of poorer health outcomes across all seven indicators and has been rising particularly steeply for families with young children.

The review focuses on seven ‘key indicators’ – infant mortality, immunisations, breastfeeding, obesity and overweight, oral health, mental health and emotional wellbeing, and respiratory health.

It highlights a number of ‘key trends’, including:

- Infant mortality – There has been a ‘significant’ decline in infant mortality in the UK over the past five years. However, in the past five years, declines have slowed from 4.3 to 4.0 deaths per 1,000 livebirths. The infant mortality rate increased three years in a row in England and Wales between 2015 and 2017 and increased in all four home nations between 2018 and 2019. The UK’s infant mortality rate is 30 per cent higher than the median rate across EU countries.

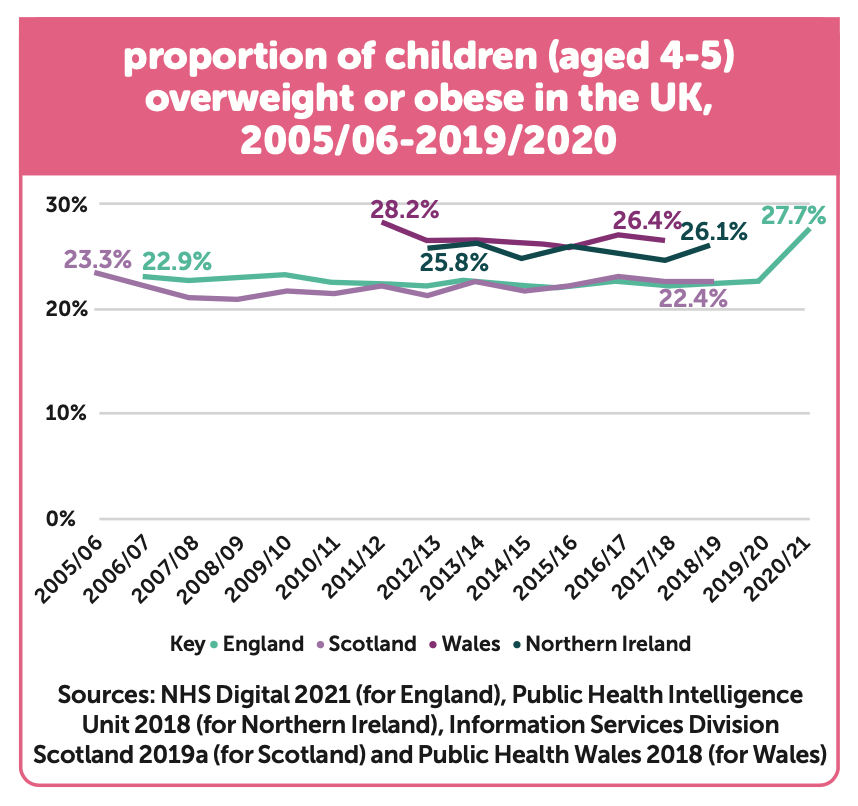

- Obese and overweight children – Until the Covid-19 pandemic, rates of obesity and overweight in four- and five-year-olds had remained broadly static since 2005, but they have soared in the past year. In England, the proportion of four- and five-year-olds classified as obese increased from 9.9 per cent in 2019/20 to 14.4 per cent in 2020/21. Around one in seven children are obese and one in 20 children are severely obese when they begin primary school.

- Vaccination uptake rates – have increased in the past 20 years but have been falling since 2014. With the 6-in-1 vaccine for one-year-olds, only Scotland and Wales meet the 95 per cent coverage recommended by the World Health Organization for herd immunity.

- Breastfeeding – There have been improvements in the proportion of mothers who breastfeed immediately after birth, but rates for those who continue to exclusively breastfeed remain far below recommended levels and are among the lowest in high-income countries.

- Dental decay – Over the past 20 years, any improvement has slowed since 2014/15.

- Respiratory health – Evidence suggests this is worsening among children. Respiratory conditions are three of the top five reasons children are admitted to hospital.

The review also reveals how inequalities vary between socioeconomic group, region and ethnicity. For instance, it finds that women from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to breastfeed than white women, and rates of infant mortality were much higher for babies from a Pakistani background in 2017 compared to those from a white British background. However, there has been a large fall in infant mortality rates in babies from Pakistani and Black-Caribbean backgrounds in the past decade.

Across some indicators of health – such as rates of breastfeeding and oral health of under-fives – the review finds that progress over the past 20 years has been maintained largely as a result of targeted national programmes. It refers to the Scottish National Infant Feeding Strategy, Sure Start – which it says led to ‘major health benefits for children from the most deprived neighbourhoods’ – and national oral health programmes in Scotland and Wales.

The authors say that, ‘The success of these interventions demonstrate that improvements in young children’s health are possible with sustained policy effort.’ The review concludes that the health of young children is at a ‘critical point’.

It recommends action on four fronts: a reassessment of whether young children are receiving adequate universal healthcare services; further development of integrated services that meet both the health and non-health needs of young children and their families; action to address child poverty; and research to explore the associations between poor health and place, ethnicity, and level of deprivation.

Dr Dougal Hargreaves, reader in Paediatrics & Population Health at Imperial College London and co-author of the review, said, ‘The concerning trends we present in this report reflect a failure to put the needs of babies and young children first. Greater investment in the early years is key to the Government aims of achieving a healthier, fairer, more highly skilled and productive society. While it’s encouraging to see this recognised in recent Government policies, it’s essential that resources match the scale of the problems we face.’

Carey Oppenheim, early childhood lead at the Nuffield Foundation, added, ‘There is such a clear link to levels of poverty and deprivation that action to tackle child poverty also needs to be a policy priority if substantial progress is to be made.’

An action plan to build a fairer future for children in the North

According to Child of the North, the pandemic has ‘accelerated’ child poverty in the North, caused a rise in child obesity and mental health issues and negatively impacted educational inequalities due to a drop in take-up of funded places and pupils missing more schooling than their peers in the South.

It finds that during the first lockdown period, just 7 per cent of children who had previously attended early years settings continued to do so (when settings were only open to children of key workers and disadvantaged children).

Other key findings from the report by the Northern Health Science Alliance (NHSA) – a partnership that links ten universities and ten NHS Teaching Trusts – reveals:

- Children living in the North are more likely to die under the age of one.

- Both relative and absolute poverty are expected to rise ‘sharply’ in the North in 2021/22 due to illness from Covid-19, long Covid and job loss.

- New mothers living in the North were more likely to experience poor mental health as they spend a month and a half longer in lockdown than the rest of England.

- Tooth decay among five-year-olds is more prevalent in the North West.

- Food insecurity is higher in households in the North of England.

The authors of the report put forward a set of recommendations which they said should ‘form the basis of an action plan to build a fairer future for children of the North after Covid-19’; they include taking immediate measures to tackle child poverty, increasing Government investment in welfare, health and social care systems and through focused investment in early years services including health visiting.

Professor of epidemiology at the University of York and co-lead author of the report Kate Pickett said, ‘Levelling up for the North must be as much about building resilience and opportunities for the Covid generation and for future children as it is about building roads, railways and bridges. But the positive message of this report is that investment in children creates high returns and benefits for society as a whole.’

Responding to the report, a Department for Education spokesperson said, ‘Our ambitious recovery plan continues to roll out across the country, with £5 billion invested in high-quality tutoring, world-class training for teachers and early years practitioners, additional funding for schools, and extending time in colleges by 40 hours a year.’