The Education Policy Institute (EPI) report, Early years workforce development in England, has found little evidence that recent government policies have improved the qualification levels of the early years workforce and said that the last policy to have a positive impact on qualifications was the Graduate Leader Fund, which was withdrawn in 2011.

It states that the Government lacks a long-term strategy to develop the early years workforce, which is key to improving the quality of early years education and supporting the outcomes of disadvantaged children.

The Government should revive the Early Years Workforce Strategy, which provided an overarching framework for policy, early years qualifications and funding.

Its decision in 2018 not to proceed with the graduate feasibility study ended the Government's commitment to grow the graduate early years workforce.

The EPI also said that information on career paths and qualifications for early years workers in England is highly fragmented and often inaccessible. The Government should set up an online data collection system for all early years workers, similar to a model in the United States, so that practitioners, providers and others would have access to information on qualifications, skills, career paths and training.

The early years workforce is suffering a well-documented recruitment crisis, with low-qualified and low-paid staff leaving the sector to work in areas such as retail, as research by the EPI last year found.

The EPI’s latest report aimed to examine four major government policies to see what impact they have had on the early years workforce.

These were: the Graduate Leader Fund (GLF), which ran from 2007-11; the introduction of minimum GCSE grades for workers; the expansion of the two-year-old entitlement; and the expansion of the three- and four-year-old entitlement.

Its findings show that the GLF, brought in by the previous Labour government in 2007 and scrapped by the coalition government in 2011, was the only policy successful in raising the level of qualifications among early years workers. Significantly, it was also able to raise the number of staff with minimum Level 3 qualifications and above.

However, between 2013 and 2018, after the funding was no longer ring-fenced, qualifications failed to improve, and fell or remained static.

Commenting on the new findings, Dr Sara Bonetti, director of early years at the EPI and author of the report, said, ‘Policymakers frequently make pledges on providing quality early years education for families, but this can only be realised if there is a highly-qualified workforce in place to deliver it. ‘This report shows that many interventions over the last decade have failed to do enough to either attract those with higher qualifications into the sector or develop the skills of existing workers.

'The Government should draw lessons from those policies that have been successful and develop a long-term plan for upskilling workers for the new decade. Failure to secure the workforce could threaten the quality of early years provision, and risks widening the attainment gap.’

Key findings

GRADUATE LEADER FUND

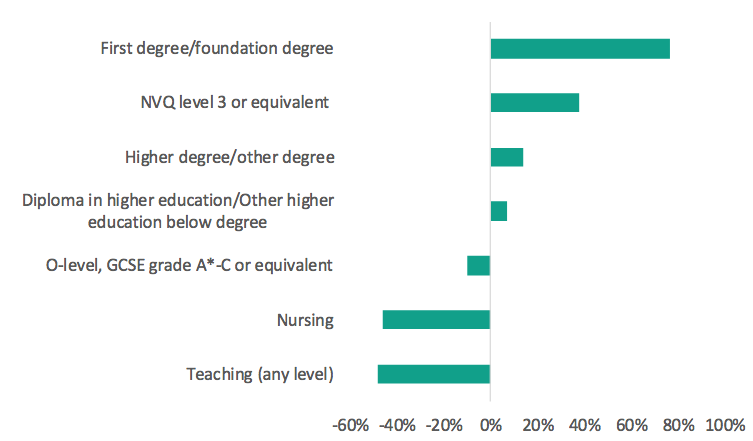

- The GLF was successful in raising early years worker’s qualification levels.

- Between 2007 and 2011, when ring-fenced funding was £305m, the number of workers holding a degree or a foundation degree rose by 76 per cent, from 16,500 workers to 29,100 workers.

- The number of early years workers holding a Master’s or equivalent rose by 13 per cent.

- In line with the fund’s aims, the rise in degree-qualified workers was mainly in the private, voluntary and independent (PVI) sector.

- The proportion of degree-qualified professionals rose by 5 percentage points, from 7 per cent of PVI staff in 2007 to 12 per cent in 2011.

- There was also an increase in qualification levels across the board. For example, between 2007 and 2011, the number of workers with a diploma in higher education rose by 7 per cent, (from 16,200 workers to 17,300).

- Those with NVQ level 3 or equivalent increased by 38 per cent (from 86,100 workers) to 118,800.

- Those with a GCSE A* - C grade or equivalent as their highest qualification fell by around 10 per cent (from 46,500 to 41,900).

NUMBER OF WORKERS QUALIFIED TO DEGREE-LEVEL OR ABOVE, 2006-13

Source: Early years workforce development in England - Key ingredients and missed opportunities, EPI

GCSE REQUIREMENT

- The GCSE requirement made it harder to recruit staff that could be counted in ratios.

- Recruitment difficulties overlapped with the expansion of childcare for two-year-olds in 2014 and in 2016-17 for three-and four-year-olds, stretching the sector's capacity.

EXPANSION OF CHILDCARE ENTITLEMENTS

- Multiple changes to the sector across the entitlements' expansion period, with an increase in the total number of workers and some changes in the demand for staff with different levels of qualifications.

- Other policy changes, e.g the change in the National Funding Formula and introduction of the National Minimum Wage pulled the workforce on different directions, making it difficult to disentangle the impact of each individual policy.

Josh Hillman, director of Education at the Nuffield Foundation said, ‘Previous Nuffield-funded research has shown that a highly-skilled early years workforce can significantly boost children’s outcomes. Yet this latest report suggests that short-term and fragmented government policies have done little to support early years staff in improving their qualification levels. It is clear – from the success of the Graduate Leader Fund – that only evidence-based, long-term policy that is sufficiently funded, can bring about real improvement in early years education.’

‘Lost decade’

Sector organisations called for urgent action and said that the report was yet more evidence of the need for long-term investment in the sector and an increase in early years funding rates.

Neil Leitch, chief executive of the Early Years Alliance, said, ‘What does it say about the Government's approach to the early years that this report found the last effective policy for improving the sector’s workforce qualifications was abandoned almost ten years ago?

‘While higher qualifications are no guarantor of quality – passion, a caring disposition and an in-depth understanding of child development are all equally as vital – if the Government is to argue that we should be aiming for a well-qualified workforce, there is simply no excuse for the current lack of strategy.’

‘We need the best people working in this sector, and that means paying a fair wage and ensuring they have a clear route to career progression. If the Government wants to avoid another lost decade, then ministers need to set out a clear strategy and start funding the early years properly.’

Purnima Tanuku, chief executive of National Day Nurseries Association (NDNA) said, ‘An abundance of research shows that a highly qualified and experienced early years workforce improves outcomes for children and has a positive impact on their future attainment and life chances.

'The fact that the Graduate Leader Fund increased qualifications across the board, not just at degree level, shows what can be achieved when investment is made and careers in early years are promoted.

‘Sadly, we have seen the funding cap create challenges for employers to be able to reward staff sufficiently for progression. Our research tells us that employers are finding it impossible to maintain sufficient differentiation between pay bands for those achieving Level 2, Level 3 and degrees due to the increase in the National Minimum Wage. That has seen many qualified workers leave the sector for better pay or conditions in areas like retail.

‘This is another clear case for ministers to provide sufficient investment. We need to see urgent action on this workforce crisis or risk seeing a lost generation of skilled and passionate staff that could negatively impact on sufficient childcare to deliver the funded offer.’

Liz Bayram, chief executive at the Professional Association for Childcare and Early Years (PACEY), said, ‘This report reminds us that a properly funded, long-term workforce development strategy that supports more practitioners to grow their qualification levels and pays them a salary commensurate with the important job they do does work. We need this Government to focus on how it will improve the funding the early years sector receives, so that it can make the investment it so desperately wants to in upskilling its practitioners.'

Deborah Lawson, general secretary of Voice, the union for education professionals, welcomed the report’s call to revive the Early Years Workforce strategy.

‘Is it any wonder there’s a recruitment and retention crisis in the early years sector? The Government must fully fund the expansion of early years and childcare to ensure that all types of providers are sustainable, and implement an early years and childcare workforce strategy that is supported by a clear pathway and national pay structure,’ she said.

Teaching unions joined in the call for the Government to commit to long-term investment in the early years workforce.

Kevin Courtney, joint general Secretary of the National Education Union, said, ‘This careful and detailed report shows that while early years provision has grown in size since 2010, it still suffers from serious issues of quality – issues which are the responsibility of Government.

‘Government should learn the lesson of this report: serious change begins with funding, and with a sustained programme to improve workforce qualifications. Those who work in the early years sector will welcome opportunities to enhance their knowledge and skills, and to enter a secure and rewarding career.’

James Bowen, director of policy for school leaders' union NAHT, said, ‘Over the last decade the Early Years sector has been buffeted by a raft of conflicting policy measures from central Government. What we now need to see is a strong commitment to long-term investment in the early years workforce so that all professionals can access high quality professional development and children get the very best possible provision.’

Angela Rayner MP, Labour’s shadow education secretary, said, 'This Government is failing to provide the investment and support necessary to make high quality early years education available for all.

'Highly qualified staff are essential to improving outcomes for children, but that means giving staff a fair wage and the opportunity to progress.

'It is time for the Government to adopt Labour’s plan for free, universal, high quality early years, including support for all staff to get the qualifications they need.'

A Department for Education spokesperson said, 'We have invested £20 million to improving training and development for our early years workforce, particularly targeted at disadvantaged areas.

‘We have also worked with the early years sector to support progression through better qualifications, more apprenticeship opportunities and ensuring there are routes to graduate level qualifications.’

- Read more on the report from our columnist Natalie Perera, executive director and head of research at the EPI, in Nursery World on Monday.