Negative stereotypes are rife, including that working in early years is ‘just babysitting’, ‘playing with toys all day’, and that ‘there’s no skill in the job’.

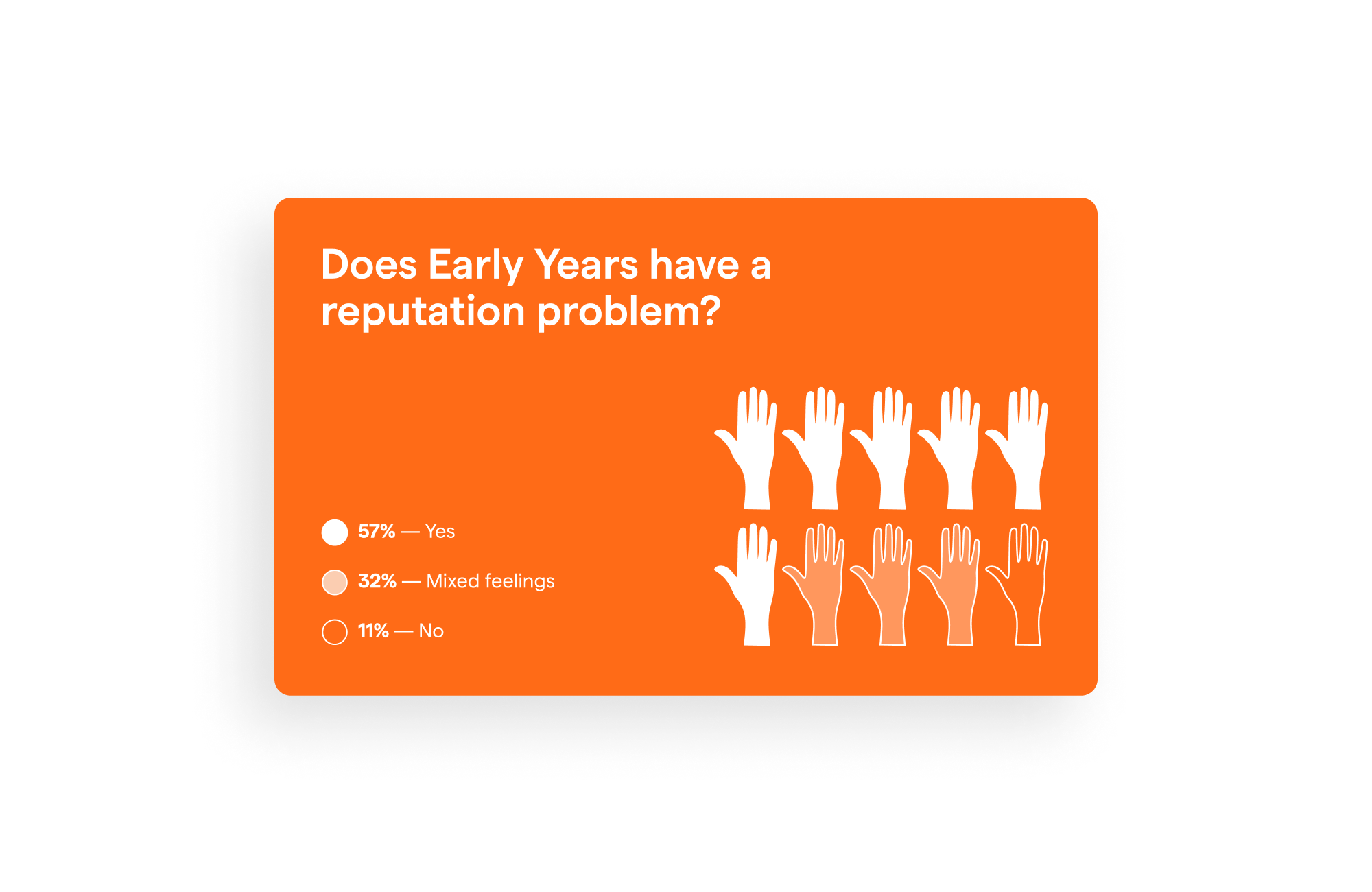

More than half also believe that the early years has a reputation problem.

Respect the sector – The Early Years Reputation report is based on findings from an online survey carried out last month by Famly, which received 740 responses.

Key findings:

- 95 per cent of respondents do not feel respected by politicians or policy makers

- 69 per cent feel they lack respect from wider society

- 86 per cent are currently facing difficulties recruiting staff

The lack of respect feeds into early years workers’ views of their jobs, with 41 per cent saying they have mixed feelings. Just 39 per cent said they were feeling positive overall about working in early years, with just 12 per cent saying they are very positive. The majority, more than 41 per cent, have mixed feelings about their work.

‘And this tension between a vocation they love and a job that is becoming increasingly demanding, was clear in the responses. “Whilst I love what I do,” one person said, “at the moment it feels so negative always,” the report said.

Report author Matt Arnerich acknowledges that for many the findings about early years stereotypes are nothing new and will not be a surprise for many.

But he said, ‘It’s time to stop the false equivalence that early years settings cannot juggle the twin objectives of getting more women back to work and delivering high-quality early education at its most important phase. Other countries do it, and it is time the UK finds its way. Negative stereotypes breed a lack of respect. That lack of respect prevents grown-up conversations about funding and stalls recruitment. If we truly care about giving young children the best possible start to life, we need to break that cycle.’

One respondent said, ‘We are told we are professionals with professional knowledge - the first line of the EYFS says we have the most important job in the country and yet the wages are less than that of a factory worker.’

Another said, ‘I think we’re an invisible workforce. Everyone knows we are there but don’t fully understand what goes into being a quality educator and providing so many opportunities and experiences for children in a week.’

These mixed feelings are reflected in the words that early years workers used to describe working in the sector. When asked to choose from a varied list of words, 77 per cent said ‘rewarding’, while a similar proportion said ‘stressful’ (75 per cent).

Other words were ‘tiring’, (70 per cent), ‘frustrating’ (58 per cent) and ‘fun’ (50 per cent).

But when respondents were also asked to choose their own adjectives, many of them were negative, with ‘undervalued’, ‘underpaid’ and ‘ignored’ common.

One anonymous respondent said, ‘[Working in early years is] soul-destroying; I have earned minimum wage for eight years.’

Those who have worked in the sector the longest were more likely to have negaitive feelings about the job. Mangers said they felt ‘lonely’ – 16 per cent, compared to 5 per cent of practitioners.

The report’s recommendations include using educator or teacher to refer to those who educate

- Using ‘educator’ or ‘teacher’ to refer to those who educate birth to five-year-olds

- An immediate review of funding rates so that they match the cost of delivery

- Public campaigns to address the root cause - a lack of understanding about the vital importance of a child’s early years and the workers who support it.

Commenting, Neil Leitch, CEO of the Early Years Alliance, said, ‘It is disappointing, but sadly not at all surprising, that 95 per cent of respondents don’t feel respected by policymakers and politicians. For far too long the early years sector has been treated appallingly by the government, not only in terms of the funding the sector receives, but also the way that our workforce has been persistently disrespected and undervalued by policymakers.

‘Despite a mountain of research highlighting how valuable early educators are in supporting children to develop skills and learning that will stay with them for life, the sector continues to fall further and further down the government’s priority list.

‘The fact that that staffing difficulties were listed as the biggest concern for professionals highlights just how bad the current recruitment and retention crisis, which has largely been driven by both low pay and the continued lack of respect for early education in this country, has become.’

- Download the full report at https://www.famly.co/guides/respect-the-sector

- Watch the video at https://vimeo.com/726969938