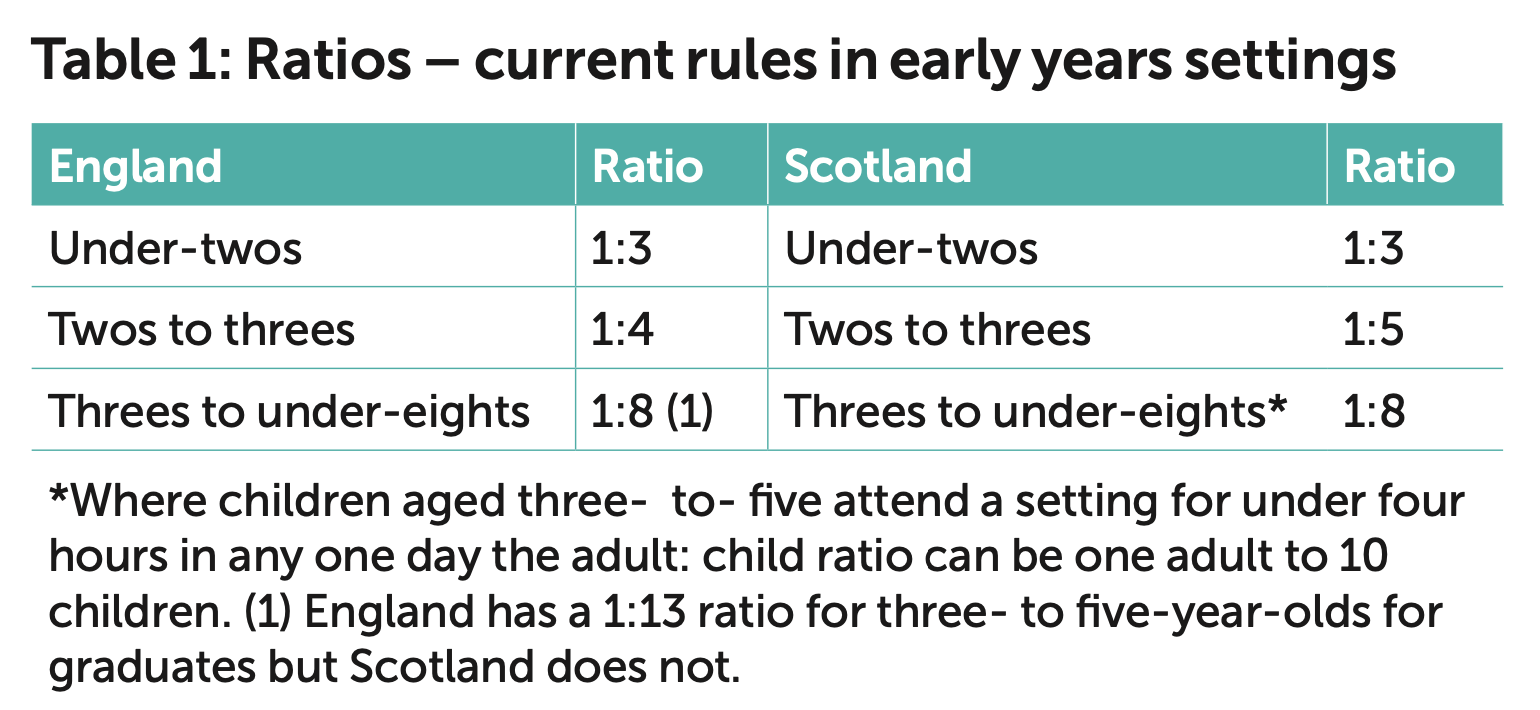

- Scotland and England funding and regulations not comparable

- Ratios dubbed ‘a red herring’ that will not ease costs

For the second time in a decade, ministers view raising the number of children staff care for in early years settings as the answer to making childcare more affordable, while the sector and parents have once again overwhelmingly mobilised to oppose the move.

Children and families minister Will Quince has confirmed a consultation will be held ‘before the summer’ on ‘mirroring’ the Scottish model – a maximum ratio of one adult to five two-year-olds, instead of the current ratio of one to four for two-year-olds.

The Government argues that one to five works in Scotland, so why not in England?

However, on closer inspection it is not an easy comparison to make, with Scotland using different regulation and funding models.

Jane Malcolm, National Day Nurseries Association (NDNA)national policy manager for Scotland, told Nursery World, ‘We’ve had this ratio for over 20 years. It’s like comparing apples to pears – it’s a very different system in place to ensure quality for children. It’s not just a numbers game.’

The ratios themselves are not statutory in Scotland, they are recommended by the Care Inspectorate. However early years settings are expected to maintain them.

‘The Care Inspectorate expect to see those ratios and they wouldn’t change them permanently,’ she said.

There is some flexibility around ratios, for example if staff are off sick, but this is agreed on a case-by-case basis by the Care Inspectorate with the setting. This happened during Covid.

‘What they might do is vary senior staff members, for example if they have a teacher but are a couple of practitioners down,’ she said.

Scottish registration and qualifications

All staff working in early learning and childcare (ELC) must register with the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC).

‘You cannot work in childcare without this registration,’ Malcolm said. ‘The SSSC makes a difference because you’re registered as a professional. It’s like teachers being registered with the General Teaching Council. Practitioners working in ELC must register as a support worker, practitioner or lead practitioner. Even at entry-level you have to register because you are working towards the qualification minimum of SCQF Level 6 / SCQF Level 7 for practitioners. If you come in as an unqualified member of staff you register with the SSSC with a condition that you complete a qualification to a minimum of SCQF level 6 / SVQ level 2 / NC Childhood Practice for a support worker, or SCQF level 7 / HND Childhood Practice for a practitioner, within five years of registration.

‘The registration maintains a high-level of quality because you have to commit to CPD through a portal post-registration – there’s a system that ensures practitioners are keeping their practice up-to-date.’

‘Deputy managers and managers must be working towards a degree in childhood practice. It’s a degree-led profession in Scotland. It’s the same for everyone whether a maintained or PVI setting.

‘There are a lot of things going on behind the scenes that make the one to five ratio work,’ she said.

Jonathan Broadbery, the NDNA’s director of policy and communications, said ‘the minister should not be looking at ratios in other countries in isolation, but in the context of their frameworks and how early years education and care is funded. You can’t just pull a lever marked ratios and produce savings at the other end of this complex system.’

Nursery group perspective

Thrive Childcare and Education CEO Cary Rankin has experience of both systems, with 26 of the group’s 46 nurseries in Scotland. Commenting on the Scottish system, he told Nursery World, ‘We’ve been operating on those ratios for as long as they’ve been a requirement and no-one knows any different. I don’t recall a conversation with anyone around the business cross-borders, “Why do they do it differently?”

‘What the discussion has absolutely raised, is whether the one to five ratio is the right ratio to operate at, more so post-Covid where the needs of children have changed quite significantly. That has become a more notable conversation – about how our colleagues are coping with the [increase in] volumes of children with additional needs. Whether you’re on a 1:4 or a 1:5 the important thing is how skilled or capable are the individuals looking after those children.’

There were other avenues the Government should explore first, such as adding early years workers to the Skilled Workers Visa, he said. Currently early years workers do not appear on the shortage list for occupations.

‘The Government in my view are focusing on the wrong thing – ratios – rather than the funding, and the list that allows workers to come and work in the UK. One of the biggest issues is recruitment, and the ability to staff our nurseries. Ratios is taking away the importance of funding and recruitment. [Ratios] is a red herring.’

Rankin said a huge number of staff had left because of Brexit and Covid and wanted to come back, and that was ‘a critical point’.

Differences in funding

The difference in funding between Scotland and England is ‘stark’, Rankin said, citing rates from Aberdeen City council, which paid providers £5.45 for three-to five-year-olds in 2021-22.

‘All local authorities are above £5, and most are heading for £6. Some local authorities are providing rates for meals. It’s close to the hourly rate we charge parents.’

Malcolm also points out that average funding is higher in Scotland for three-and four-year-olds varying from £5.05 to £6.80, with an average of £5.30, she said.

In England in 2022/23, the average rate paid to local authorities will be just £5.05.

‘Funding hasn’t kept up with inflation or wage increases,’ said Rankin. ‘It goes right back to the funding and unless they address that it’s not going to change for providers or parents.’ He also highlighted that Scotland gave extra funding for providers during Covid.

Flexibility

During the pandemic settings were able to use exemptions from ratio regulations to cope with staff absences during Covid – was this something that Thrive did?

Rankin said, ‘From time to time we were forced to because of sheer numbers of absences. ‘We risk-managed it, but we did it few and far between. Ultimately this is about preventing a negative impact on children on a day-to-day basis. That is the overall objection [to ratio changes] across the sector.’

How does he think nurseries would react if the change does come in, and are there any circumstances where it could work?

‘If we have no choice in the matter, providers may continue to run at 1:4, because they feel it is the best outcome for children. That is the general feel of the sector. What it might give us is flexibility in situations with significant challenges, but we won’t want it to become the norm. Even with a 1:8 or a 1:13 [for three- to- fives], most people operate on a 1:8. It’s a very dangerous thing to change.’

If the Government does relax early years ratios, just 13 per cent of nurseries and pre-schools in a recent Early Years Alliance survey said they would regularly or permanently use the new ratios, with a similar percentage predicting moderate or significant financial benefits from ratios changes.

‘It could offer us some semblance of flexibility, while we wait and lobby for a fairer rate,’ said Kirsty Lester, posting on Champagne Nurseries on Lemonade Funding. ‘We know we’re underfunded, and it would be easy to scream about the ratio change as a cheapskate way of easing costs for parents. Just because they set a minimum, it doesn’t mean we have to adhere to it, but we could embrace it as a way of taking the pressure off if it allows us to manage and assess the risk of our own practice.

‘For instance, two members of staff for eight two- year-olds; if we had nine, we don’t immediately have to add another staff member because one child makes very little difference to the dynamic.

‘But if it was 15, all under three, we would all put four staff in, even though we don’t have to because we know that would be unsafe.’

Broadbery said, ‘Providers know what is best for their own particular circumstances and in some cases, giving more flexibility to ratios could help some settings. They can still use the “emergency circumstances” clause in the EYFS should they need to address short-term issues but there is a lack of clarity about how long and in what circumstances these would be accepted.’

Childcare costs

Sector organisations and settings have also dismissed the Government’s rationale for changing ratios – that it would lower childcare costs for parents.

Rankin said, ‘There is an obvious saving on a gross margin basis, but providers are saying no because of the impact on children and the tough regulatory environment. And it would touch the tip of the iceberg in terms of inflationary costs,’ such as rises to utilities, and the price of food.

He added, ‘The argument is they’re doing it in Scotland, but it’s a very different support structure and funding rate.’

Just 2 per cent of respondents to the Alliance survey believed the rule change would enable them to lower fees for parents.

The Alliance said its findings show that if the Government does push ahead with its plans most settings won’t change their ratios, even fewer would do it regularly, fewer still would save any money from it and hardly any would reduce parent fees as a result.

Opposition

There seems little appetite among providers or parents to move to lower ratios.

The Alliance survey found 87 per cent of nurseries and pre-schools are opposed in principle, with 80 per cent ‘strongly opposed.’ It also predicts any change could lead to a mass exodus of early years practitioners from a sector already facing recruitment challenges – 75 per cent said they would be likely to leave their current setting if ratios were relaxed there. A snap poll from parenting group Pregnant then Screwed of 17,000 parents on Instagram found 85 per cent of parents would be opposed, even if led to lower costs.

Meanwhile, a parliamentary petition against the plans led by the family of Oliver Steeper, who tragically died in an incident at nursery, has so far amassed nearly 62,000 signatures.

In its official response to the petition, the Government said it was ‘moving to the Scottish ratios for two-year-olds on the basis that Scotland has a similar childcare system to England, we have no evidence to suggest that the Scottish model is unsafe, and evidence shows high parental satisfaction rates. England’s statutory minimum staff to child ratios for two-year-olds are among the highest in Europe.’

However, Rankin also pointed out there has been no research or evidence done to compare the two different early years systems in Scotland and England. ‘The Government ideally should be looking at this. Don’t rush into it.

‘There is no empirical evidence either way to suggest that one way is better than the other. There are so many variables.’

The response continues, ‘Whilst these proposed changes to ratios would amend the existing statutory minimum requirements, providers would continue to be able to staff above these minimum requirements…These changes would hand greater autonomy to settings to exercise professional judgement in the way in which they staff their settings, according to the needs of their children, and help as many families as possible benefit from affordable, flexible, quality childcare.’

Broadbery added, ‘Just tinkering with ratio restrictions in isolation cannot be a solution to wider challenges within the sector.

‘Now is certainly not the time for us to be looking at providing children with less support.’