- The closure of the furlough scheme and reduced demand for places have created ‘uncertainty’.

- Despite reduced revenues for some providers, they are still holding on to staff due to the workforce shortage.

Now the furlough scheme has come to a close and with demand for childcare places down on pre-Covid levels in some areas, early years providers may be faced with difficult decisions.

The Education Policy Institute (EPI) and National Day Nurseries Association (NDNA) have warned that providers face a ‘very uncertain situation’ coming into autumn.

Sara Bonetti of the EPI told Nursery World, ‘We don’t expect to see an impact of the closure of the scheme on settings until at least November as their decisions will be based upon demand for childcare, which could continue at existing levels or fall further if parents lose their jobs or decide they can continue to have their children with them while they work from home.’

The think-tank and early years organisation said in the summer that ‘uncertainty for the sector would not just finish at the end of September when the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme [CJRS] came to a close’.

A report was based on results from its last quarterly survey of early education and childcare providers in Great Britain, undertaken in May, which received 478 responses. It was part of a year-long study to gain insight into the impact on the early years workforce.

Furlough

It is estimated that one million employees nationally were still on furlough when the CJRS ended on 30 September.

Furlough was introduced in March 2020 after Covid-19 forced large parts of the UK economy to close. Under the scheme, the Government paid towards the wages of employees who could not work, or whose employers could no longer afford to pay them, up to a monthly limit of £2,500. Initially, the Government paid 80 per cent of employees’ usual wage, but this dropped to 60 per cent from August 2021, with employers topping up the additional 20 per cent.

Official statistics show that 1.3 million staff were benefiting from the CJRS as of 31 August – a month before the scheme closed. Figures on the number furloughed up until the end of September are due to be published at the beginning of November.

While there is no breakdown of the data for the early years sector, the HMRC figures indicate that more men than women were on furlough through May-August this year, which it says ‘reflects decreases in the number of jobs on furlough in sectors which have a higher proportion of female employees’.

Research also suggests providers relied upon the scheme much less than they did at the height of the pandemic, when as many as seven in ten staff were on furlough, according to EPI and NDNA survey findings. This was mainly due to settings being closed or only providing care to a handful of children whose parents were considered as ‘key workers’.

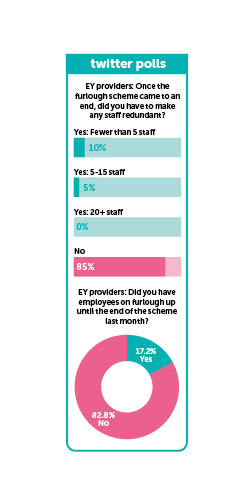

One of three snap polls on Nursery World’s Twitter page found that just 17 per cent of early years providers had staff on furlough at the end of September. The poll, which ran between 8 and 12 November, received a total of 29 responses.

One of three snap polls on Nursery World’s Twitter page found that just 17 per cent of early years providers had staff on furlough at the end of September. The poll, which ran between 8 and 12 November, received a total of 29 responses.

This echoes findings from the EPI and NDNA’s final report, which revealed providers planned to place 1 per cent of staff on full-time furlough and 7 per cent on part-time furlough during the last four months of the CJRS due to reduced demand for places, which according to the Department for Education continues to be down nationally.

Childcare demand

The most recent statistics reveal that an estimated 751,000 children were attending settings on 14 October, about 59 per cent less than normal for the time of year.

However, the DfE said that due to many children attending settings on a part-time basis, it would not expect all children to be in attendance on the day of the data collection.

On a typical day in the autumn term, it expects attendance to be 912,000, due to different and part-time patterns of childcare during the week. The Government department estimates that 751,000 children currently attending early years settings is approximately 82 per cent of the usual daily level.

While the figures represent a rise on the previous statistics in September, they are still below attendance pre-Covid.

Courteney Donaldson, managing director of childcare and education at Christie & Co, said it was seeing a mixed picture in terms of occupancy.

‘Across the UK, while some nursery owners report that they are trading ahead of pre-Covid occupancy levels – many have waiting lists in place because they don’t have adequate staff to meet this demand – other providers are seeing low levels of occupancy. It really comes down to individual settings, the parents they serve and the local micro economic factors’, she explained.

‘Some of our operators are saying their occupancy has fully recovered and is at higher levels than they have seen for a long time. A lot of nurseries that tell us this are in slightly more affluent, suburban areas with high density of housing and where parents are working from home. Because we have seen some nursery closures, children who attended these settings need somewhere else to go.

‘I was speaking to one operator where the majority of parents work in retail, the high street and manufacturing – they can’t work from home.’

Snapdragons Nurseries, a group of ten settings, told Nursery World that almost all are back to pre-pandemic numbers, and its newest site, opened last October, has steady demand.

According to Christie’s Donaldson, settings in deprived areas are facing the greatest challenge with occupancy, which could be because parents have lost their jobs. Demand is also down for those in central city business district areas and Zones 1 and 2 in central London.

‘These settings will likely have to make some difficult decisions in regard to staff now that furlough has ended, especially if there is insufficient demand as the roles may no longer be required’, Donaldson said. ‘Due to the ongoing shortage of qualified staff, operators will want to retain their furloughed workforce, but if they haven’t got the occupancy, how do they now fully fund those staff when their revenues haven’t recovered fully?’

The majority (85 per cent) of providers that responded to Nursery World’s Twitter poll said they had not made any staff redundant since furlough ended. Of the 20 providers that took part, 10 per cent had let go of fewer than five staff, and 5 per cent five to 15 employees.

The transition back to the workplace

Another challenge early years providers face is reintroducing previously furloughed staff back to settings, particularly when some employees might have been off for the maximum 18 months.

Research by Nursery World suggests that staff returning to work from furlough have struggled most with Covid rules and general day-to-day care.

Snapdragons finance director Jennifer Biddel said some of its staff were concerned about returning to work due to the lack of social distancing in early years, but most were comfortable with the ‘strict’ bubbles, reporting and cleaning procedures in place.

The nursery group has initiated four-day working weeks for practitioners (with staff working the same number of hours as pre-pandemic) so there is no mixing of bubbles at the beginning or end of the day, which Biddel says also benefits the wellbeing of staff.

At the height of the pandemic in March and April 2020, the nursery group furloughed 75 per cent of its staff team. Employees who continued to work were paid at a premium rate to recognise and reward their commitment to the children in their care. The nursery group did not use the furlough scheme this year.

‘When we re-opened all our settings in June, we initially had fewer children – some parents were nervous about returning and some were coping while working from home on furlough,’ explains Biddel. ‘We polled our staff to ask if they felt able to return and, if so, what they would be happy doing. This was because we didn’t need a full staff team so some may have needed to be flexible about their roles. Some staff opted to continue to remain on furlough in those early weeks, often because it helped them with their own childcare or other family situations, or because they felt vulnerable to Covid. We only had very small furlough claims from September to December 2020 and none in 2021.

‘We have definitely had a rise in general anxiety levels among employees, which is not related to work.

‘We have all got used to heightened cleaning regimes, handwashing, sanitising, masks and open windows, however. We have only recently returned to allowing parents inside to drop off and pick up their children.’

To thank staff for all their hard work during the pandemic and to acknowledge how stressful it has been, the nursery group is to reward all employees with a Covid Bonus – equivalent to a week’s salary – in their November pay.

CASE STUDY: Welcome Nurseries

Staff at Welcome Nurseries, a group of 53 settings, were given the choice whether they wanted to be furloughed or continue to work.

Staff at Welcome Nurseries, a group of 53 settings, were given the choice whether they wanted to be furloughed or continue to work.

‘Of the nurseries that remained open during lockdown, we asked staff whether they wanted to continue to work,’ says director Linda Cuddy. ‘The majority of our employees that live alone wanted to keep coming in so they weren’t isolated and for the good of their own mental health. Most of our nursery managers continued to come into their setting.

‘A lot of staff that wanted to be on furlough were worried about catching the virus because they lived with older family members or those that were vulnerable.’

Altogether, a third of the nursery group’s staff, around 200, were put on furlough – this included chefs in settings that were closed, as well as pregnant or ‘high-risk’ employees.

‘To make it as fair as possible, after working for a minimum of three weeks, for those who wanted to, we swapped non-furloughed and furloughed staff around,’ says Cuddy. ‘At the height of the pandemic, working in settings was very tiring and stressful. We didn’t want any employees to build up resentment for working a 40-hour week when other colleagues were at home. Apart from staff that were deemed “high-risk”, everyone came together.’

The nursery group felt it was important to check up on furloughed staff and contacted them on a weekly basis via text, WhatsApp, by phone or over Zoom.

Cuddy says since the end of furlough, they have lost a couple of staff who decided they didn’t want to work in the sector any more, but they have not had to make any redundancies.