plant of the month: horse chestnut

The stately, majestic horse chestnut must be one of the most recognisable trees, all year round, with its distinctive ‘hand’ shaped leaves, candelabra flower spikes and, of course – autumn’s abundant conker harvest.

The stately, majestic horse chestnut must be one of the most recognisable trees, all year round, with its distinctive ‘hand’ shaped leaves, candelabra flower spikes and, of course – autumn’s abundant conker harvest.

Collect all the conkers you can find to try the ideas in this month’s article – and of course, don’t forget to actually play conkers! It’s a childhood rite of passage. There are so many ways to enjoy conkers… read on!

Fact file

- Conkers are not edible, unlike sweet chestnuts, so knowing the difference is important. If you have a sweet chestnut near you, collect a few cases to show to children alongside conker cases.

- Horse chestnuts can live for up to 300 years – that might seem a long time, but many trees, including the sweet chestnut, can live for more than twice that.

- Although conker trees are common all over Britain, they are not native, and weren’t introduced until the 16th century.

- Conkers are a horse chestnut tree’s seeds – they are much bigger than most of the seeds that we see, and can’t float away on the wind. Instead the horse chestnuts rely on just one or two of the hundreds of conkers that fall from a single tree finding a place of their own to grow.

Myth, magic and culture

Some horse chestnut have a basis in truth: the chemicals in the conkers can be extracted and used as medicine for horses, as well as an ingredient in starch that was used in the preparation of armaments in the Second World War in order to avoid using food crops. The centre of conkers can also be crushed up and made into washing detergent, and you may well see them promoted in eco-products.

Superhero feature

No question about this – conkers! Given how deep-rooted the game of conkers is, I was surprised to learn that conkers has only been played for a couple of hundred years; in fact, the horse chestnut is a relative newcomer. Make holes through the centre of the conkers using a knitting needle and practise threading them.

No question about this – conkers! Given how deep-rooted the game of conkers is, I was surprised to learn that conkers has only been played for a couple of hundred years; in fact, the horse chestnut is a relative newcomer. Make holes through the centre of the conkers using a knitting needle and practise threading them.

What to look for

Horse chestnut leaves are large and grow in fives, and look like a droopy, fat-fingered hand.

Horse chestnut leaves are large and grow in fives, and look like a droopy, fat-fingered hand.- The springtime flowers are very showy and grow upwards on spikes with dozens of small white blossoms touched with pink and yellow.

- Conkers grow in bright green cases, with a couple of dozen short spikes.

- The conkers burst out of their cases and drop to the ground in autumn.

Impersonators/horse chestnut in disguise

Sweet chestnuts hide their seeds in similar cases to horse chestnuts – but they are much more spiky. The seeds have a flatter shape and a clump of hairy fluff.

Sycamore leaves have five ‘points, but each point is part of the same leaf. On a horse chestnut, each leaf is separate and joined with four others at the stem.

STEM springboards

Collect handfuls of conkers and sweet chestnut cases, both open and closed. Arrange them on pale paper outdoors. What features can children observe? Open up a few of the cases to examine the seeds inside.

Collect handfuls of conkers and sweet chestnut cases, both open and closed. Arrange them on pale paper outdoors. What features can children observe? Open up a few of the cases to examine the seeds inside.- Paint numbers or letters on them.

- Use them in ten or hundred squares.

- Sort them by weight or by size.

- Use them for throwing practice.

- Fill a tall jar with conkers and ask children to guess how many there are inside of it – then count them.

- Paint them.

- Use nail polishes to decorate them – ask parents to donate colours they no longer want.

- Make natural ‘ephemeral’ artworks, create trails to follow, celebrate favourite features of the garden with a crown or border of conkers – be creative!

Horse chestnut project

- Grow your own forest of horse chestnut trees! Conkers need cold to sprout, so you don’t need a greenhouse or even a sunny windowsill.

- Collect at least a couple of dozen conkers and start by dropping all of them into a bucket of water – any that float are already dried out inside and won’t grow.

- Jam jar method:You’ll need water, lots of small jam jars or tubs, a thin knitting needle or mattress needle, some toothpicks – and a lot of patience! Use the needle to make three holes near and around the top of each conker and one at the base – you’ll want to do this yourself as it’s quite awkward to get through the shiny shell. Then children can push a toothpick into each of the three top holes. Now they fill their glass with water and place the conker over the top so that it’s suspended in the water by the toothpicks. Label the jar with the child’s name and the date. Leave the jars on a shelf or windowsill over autumn and winter, changing and topping up the water regularly. By spring, a tangle of roots should have appeared.

- Fridge method:Wrap conkers loosely in moist paper towel, seal them in their own plastic bag and place them in the fridge. Mark the bag with the child’s name and the date. Check the bags regularly – but it will be spring before there are enough roots to allow the conkers to be planted outdoors.

- Ground method:Of course, the very simplest method is to plant the conkers straight outdoors into the ground, and into pots. In autumn when the conkers are fresh, push them about a child’s index finger deep into soil or compost with the ‘eye’ facing upwards, then cover them back over. Remember to put lollipop-stick labels in each pot and garden spot, with the plant name and the date you planted it on. Water regularly and wait for spring for the first shoots to appear.

- Which method do children think will be the most successful? Take photos each week or each set of conkers, and compare and contrast as autumn and winter turn into spring and roots and shoots begin to sprout.

Horse chestnut seasonal springboards

There are lots of myths about how to make a SuperConker (baking them and soaking in vinegar being just two I remember trying as a child), but there’s plenty of fun to be had just threading them and bashing them. Each time a conker successfully mangles another one, it becomes a ‘onser’ then a ‘twoser’ and so on. Use the bucket test to separate fresh and dried-up conkers – which is best at conker battles?

There are lots of myths about how to make a SuperConker (baking them and soaking in vinegar being just two I remember trying as a child), but there’s plenty of fun to be had just threading them and bashing them. Each time a conker successfully mangles another one, it becomes a ‘onser’ then a ‘twoser’ and so on. Use the bucket test to separate fresh and dried-up conkers – which is best at conker battles?- Over winter, another of horse chestnut’s superhero features appears: its huge reddy-brown buds, which emerge much earlier than most other trees. Use secateurs to snip a few buds, if you can reach them, and let children touch and smell them. The buds are sticky and have a distinctive scent – how would children describe it?

- The flower ‘panicles’ emerge in spring and are truly spectacular, although maddeningly, they tend to grow out of reach. If you can find a tree with branches low enough, use secateurs to carefully snip off one of the flower spikes and bring it back to the setting for children to examine close up. Talk about the colours and shapes they can see. Show children a picture of a super-fancy candelabra and ask if they can see any similarities, then draw or paint the flower.

- Summer horse chestnuts are magnificent specimens. In full leaf they are havens for birds and insects and the massive canopy provides shelter for humans seeking respite from the sunshine and showers of a typical British summer. However, in recent years, a parasite called leaf miner has targeted horse chestnuts, causing leaves to turn brown, dry out and often drop off, during summer. While this doesn’t seem to unduly harm the lifecycle of the tree itself, it’s very unattractive. There is an app, called Leaf Watch, to track the spread of the leaf miner, and children might like to map affected trees they find in your neighbourhood.

A conker story

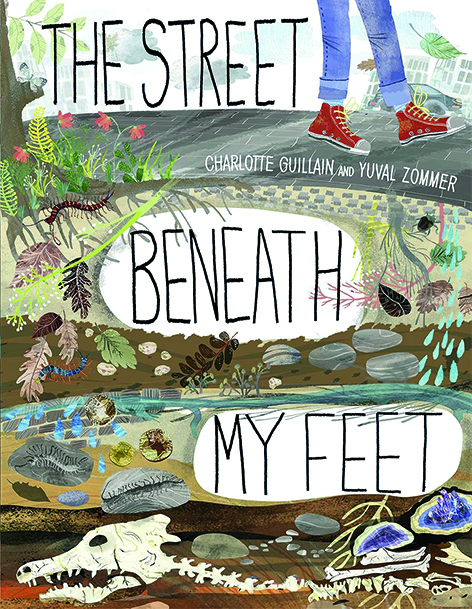

There are so many picturebooks about or inspired by conkers that I’m not going to highlight one – do an internet search and dozens will come up, including non-fiction, poetry and songs. Instead, a book I’ve really enjoyed using with children of all ages and in all kinds of contexts is The Street Beneath My Feet by Charlotte Guillain and Yuval Zommer. It’s packed with fascinating and beautifully illustrated pull-out, ‘cut through’ illustrations showing what lies under our feet in the city and the countryside.

There are so many picturebooks about or inspired by conkers that I’m not going to highlight one – do an internet search and dozens will come up, including non-fiction, poetry and songs. Instead, a book I’ve really enjoyed using with children of all ages and in all kinds of contexts is The Street Beneath My Feet by Charlotte Guillain and Yuval Zommer. It’s packed with fascinating and beautifully illustrated pull-out, ‘cut through’ illustrations showing what lies under our feet in the city and the countryside.

Next month – poppies

Next month, I’ll be exploring poppies – they won’t be in flowering in November, but if you have a few in your garden, do harvest as many of the seeds as you can.

Next month, I’ll be exploring poppies – they won’t be in flowering in November, but if you have a few in your garden, do harvest as many of the seeds as you can.