In 2016, Nursery World reported that the Council on Communications and Media of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended zero screen time for children younger than 18 months, and no more than one hour per day for children aged two to five.

The move was, in part, a preventative measure against obesity and sleep disruption, though the AAP also stressed that screen time must not be prioritised over opportunities for reading aloud, exercise, social interaction, play and sleep, and should be limited only to high-quality digital content.

Although last year the World Health Organization (WHO) echoed this advice, it is important to note that some UK experts, such as the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, defended families who may exceed these recommendations due to cramped housing, work patterns, stress and other factors, for whom ‘striving for perfect could become the enemy of good’.

While noting that ‘social and cognitive skills are better developed with another person than a screen’, the WHO’s Dr Juana Willumsen adds ‘there is no denying that screens are part of the modern era… it is how we interact that matters’.

Screen time should never be a replacement for shared storytime, but collaborative engagement between young children and their caregivers with high-quality interactive media can help to establish healthy habits for later in life and provide an enriching literary experience in itself.

DIGITAL BOOKS vs STORY APPS

I must first admit to having been tech-averse throughout most of my teaching practice (and personal life!). I preferred hand-writing notes and signs to typing, seeing it as an opportunity to model what I was trying to encourage in my young learners. I tried, too, to refrain from typing up notes on a tablet when making observations, noting how absorptive a screen can be – even as a professional tool – when one’s attention is more valuable in observing than recording.

It felt like a challenge, then, to respond to participants’ requests at February’s Nursery World Show to engage with digital picturebooks in this series. One participant’s aversion to their use in an early years setting, summed up by the maxim ‘lap, not app’, stands out in my memory in contrast to the enthusiasm of other practitioners I met.

This interested me in exploring what light recent scholarship might be able to shed in support of some practitioners’ ready embrace of the new possibilities offered by digital storytelling, and others’ keenness to maintain traditional storytime.

I have found distinguishing between traditional picturebooks, simply digitalised and made accessible via tablets or devices, and more innovative ‘story apps’, to be helpful in bridging these two, seemingly polar, approaches to technology at storytime.

I can find little benefit to the former, which lacks the fine motor book culture associated with handling traditional books, and does not enhance the reading experience for children. There is growing evidence, however, for the benefits of the latter.

KEY FEATURES OF STORY APPS

Looking carefully and exploring details

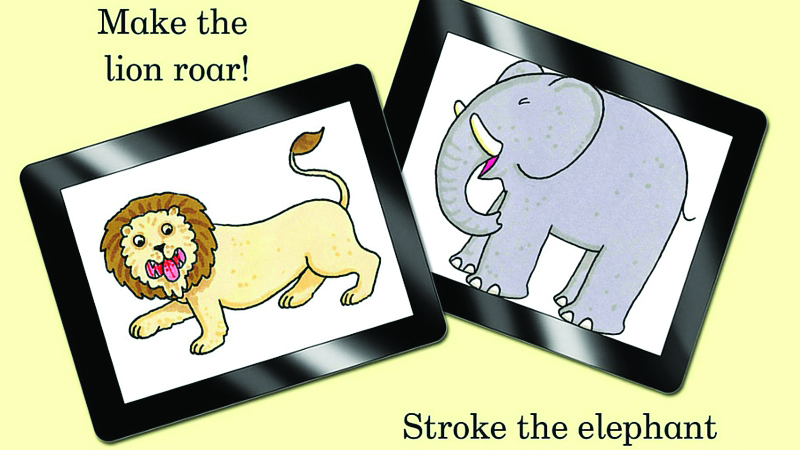

Children’s literature scholars Maria Nikolajeva and Ghada Al-Yaqout define story apps by their expansion upon the traditional picturebook ‘to include auditory, tactile, and performative dimensions’, including read-to-me functions that can highlight text as it is read aloud by the tablet or device; animation; music and background noise; games; tasks; and choice for readers as to which characters, settings or story paths they follow.

Prof Nikolajeva and Dr Al-Yaqout draw comparisons between these innovative technologies and their printed predecessors, noting in their analysis of story-app versions of classic picturebooks that while the ‘simple tasks, involving tapping on various objects to make them move, shake, fall or burst’ (available via ‘read and play’ functions) ‘may seem a game, they do exactly what we encourage children to do with picturebooks: look carefully and explore details’.

Enhancing the experience

Prof Nikolajeva and Dr Al-Yaqout praise story apps in which ‘dialogue and the various actions enhance the experience’ of engagement with a traditional book, such as in Nosy Crow’s Cinderella – in which readers can tap characters who provide additional comments on the narrative, or can participate in games or tasks which influence the narrative in a participatory way but are not required in order to enjoy or progress through the story.

They are quick, however, to warn against story apps which, rather than innovate and push the boundaries of traditional picturebook engagement, instead enter the realm of gaming, focusing ‘the user’s attention… more on accomplishing tasks than on the narrative itself’.

Digital literacy researcher Celia Turrion coined the term ‘false participation’ to describe tasks or functions of digital picturebooks which don’t increase ‘narrative complexity’ of stories or engage ‘the reader’s participation in the work interpretation process’.

The interactive features of stories like Nosy Crow’s Cinderella draw close attention to visual and textual clues about the characters and narratives, and include tasks and games which allow readers to participate in moving the story forward in the direction they choose.

PRACTITIONER ATTITUDES

Interestingly, recent research by educational psychologists Gabrielle Strouse and Patricia Ganea indicates that ‘parents’ [or teachers’ or carers’] attitudes toward digital books might influence their perceptions of children’s engagement and enjoyment of the reading sessions’, giving pause for thought about one’s own presumptions before engaging with a new digital text.

Practitioners who don’t value the potential that story apps might have for developing literacy and deep engagement with stories are less likely to model good shared reading practice – prompting, questioning, and enriching the reading experience – than their colleagues who approach the possibilities of story apps with a more open mind.

Modelling and exploring

Make sure to investigate the functions of new story apps you buy for your setting before encouraging children’s independent engagement, and explore these resources in small-group circles to observe how children learn from and with them after modelling genuine participation in their most enriching, engaging aspects.

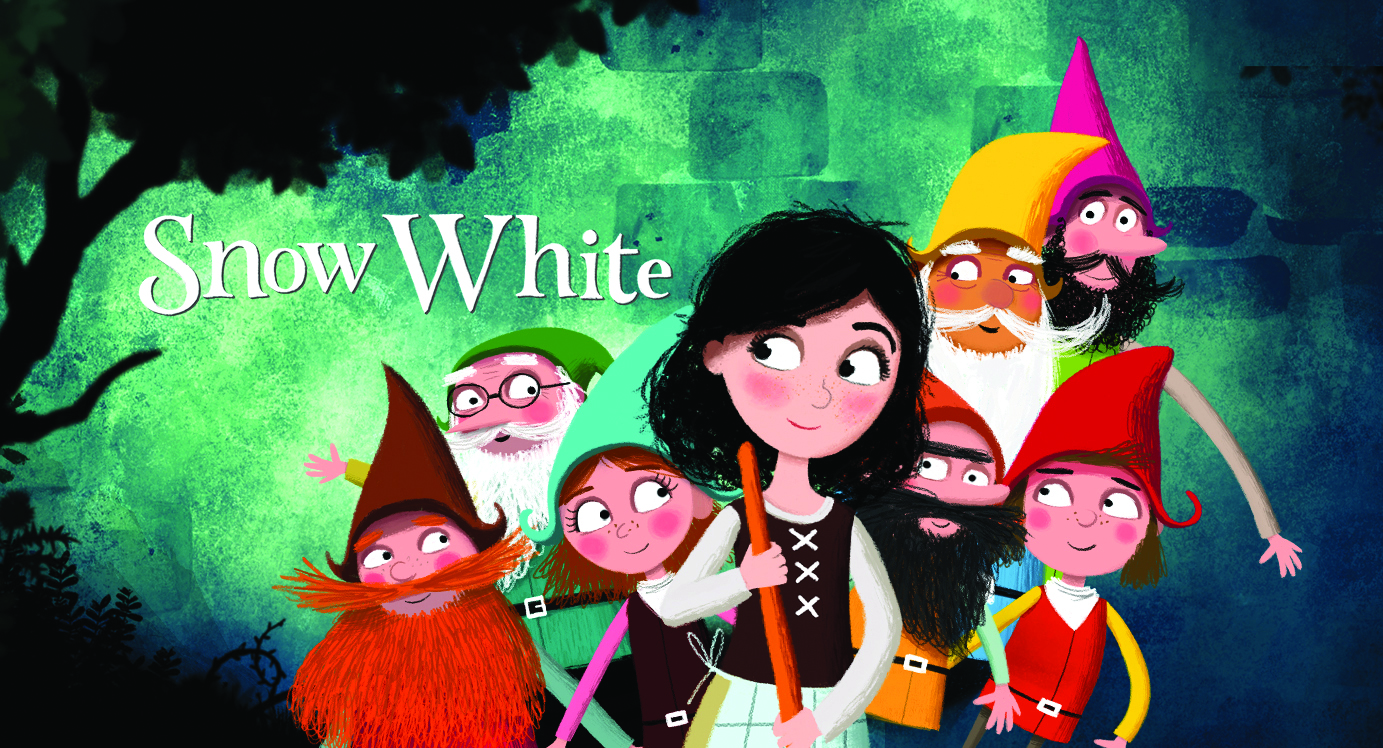

Nosy Crow’s fairytale story apps are an excellent place to begin, and really exhibit the most innovative and creative aspects of the story app’s potential.

EAL

In a study published in the journal Children’s Literature in English Language Education, EAL researchers Sonja Brunsmeier and Annika Kolb evidence the particular benefits of story apps for children learning English as an additional language. They note that ‘beginning young learners can benefit from audio narration, animation and sounds, vocabulary support and the opportunity to participate in and co-create the story in story apps’, and record that ‘being active and interacting with the story app not only helped them to get involved in the story but also to be in control of their own reading process’.

They note, ‘[The children] wanted to determine the moment when the reading aloud and animations started, they wanted to get back to parts of the text they did not understand the first time, and they appreciated having an influence on the content and language of the story. The children very happily accepted an active role in the reading process and they made use of the opportunities to adapt the story apps to their individual needs.’

Addressing possible ‘false participation’

Dr Brunsmeier and Dr Kolb provide some guidance, too, on addressing the potential for ‘false participation’, which they recognised might prove one element of attraction for children but which lacks the sound educational and developmental benefits of engagement with traditional picturebooks.

They suggest ‘tasks and activities requiring [the children] to deal with specific aspects of the story and making it necessary to engage with the language of the text’ as one way of tapping into the story apps’ educative potential.

Enriching adult direction and collaboration throughout the reading process remains, then, just as important in sharing digital picturebooks as it does with their more traditional counterparts.

Original story apps

Nosy Crow’s fairytale story apps series includes The Three Little Pigs, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, Snow White and Goldilocks and Little Bear

Nosy Crow’s fairytale story apps series includes The Three Little Pigs, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, Snow White and Goldilocks and Little Bear- Don’t Let Pigeon Run This App! by Mo Willems

- The Heart and the Bottle by Oliver Jeffers

Wuwu & Co: A magical picturebook by Merete Pryds Helle, Kamila Slocinska, Tim Garbos and Step In Books

Wuwu & Co: A magical picturebook by Merete Pryds Helle, Kamila Slocinska, Tim Garbos and Step In Books- The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore by William Joyce, Brandon Oldenburg and Moonbot Studios

Well-adapted classics

Dear Zoo by Rod Campbell

Dear Zoo by Rod Campbell- The Monster at the End of this Book (Starring Loveable, Furry Old Grover) by Jon Stone and Michael Smollin

Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson

Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson- Hop on Pop by Doctor Seuss

- Green Eggs and Ham by Doctor Seuss

Andy McCormack is an Early Years Teacher studying for his PhD at the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature, University of Cambridge

Thank you to Nursery World reader Alison Austin, who brought to my attention her difficulty in downloading some of the titles recommended in this article, and my apologies for similar difficulties some of you may have faced in trying to access them. Unfortunately, one of the drawbacks of digital picturebooks is their unreliability for purchase some time after their first publication – something I have discovered for myself since trying to track down some of these recommended texts anew, despite their longstanding installation on my reference library tablet!

App editions of Dear Zoo, Harold and the Purple Crayon, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore and The Heart and the Bottle are titles sadly no longer supported. I got in touch with Tom Bonnick, senior commissioning editor at Nosy Crow, who explained to me, too, that ‘unfortunately, an update to iOS last year caused our apps to crash, and despite our best efforts, we were unable to resolve this issue. We, therefore, took the difficult decision to permanently remove our apps for sale from the App Store, and they are now no longer available for sale.’

I’m grateful to Alison for recommending an excellent resource for choosing active apps facilitated by the Literacy Trust, to which she turned in her research for alternatives: http://literacyapps.literacytrust.org.uk/. See the ‘Literacy Apps’ website for up-to-date recommendations and reviews for new and currently supported apps available for purchase for your setting. Happy exploring!