Education is an emotive subject, and is often subject to much political reform, as those working in it will testify. Low numbers of new mothers in work, and increasing recognition of the importance of high-quality childcare, have fuelled the desire from policymakers to intervene. Austerity, then Covid-19, have more recently also shifted the policy focus.

Education is an emotive subject, and is often subject to much political reform, as those working in it will testify. Low numbers of new mothers in work, and increasing recognition of the importance of high-quality childcare, have fuelled the desire from policymakers to intervene. Austerity, then Covid-19, have more recently also shifted the policy focus.

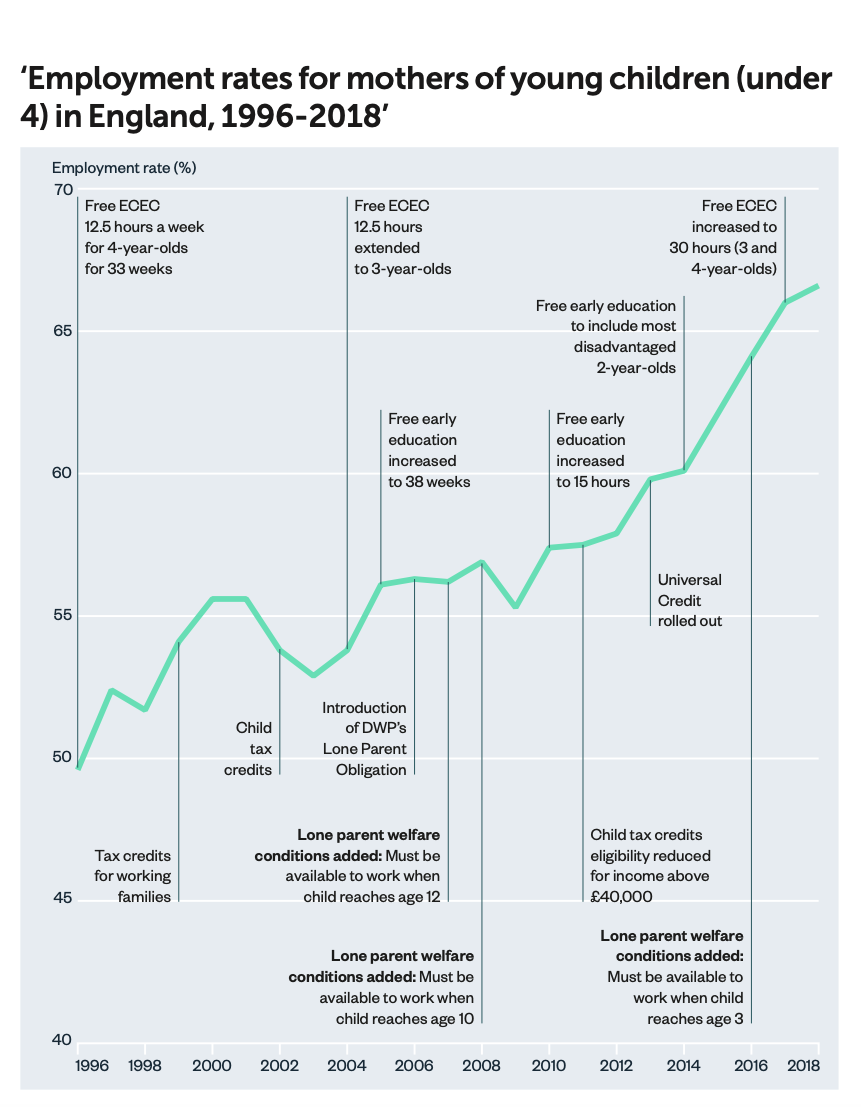

Recent policies have included the early years entitlement, in particular the 30 hours, and the effect of this, along with a flattening of support for the costs of childcare through the tax credit and benefit system and a sharp fall in the number of Sure Start Children's centres, has been to shift the focus of spending away from disadvantaged families.

WHERE HAVE WE COME FROM?

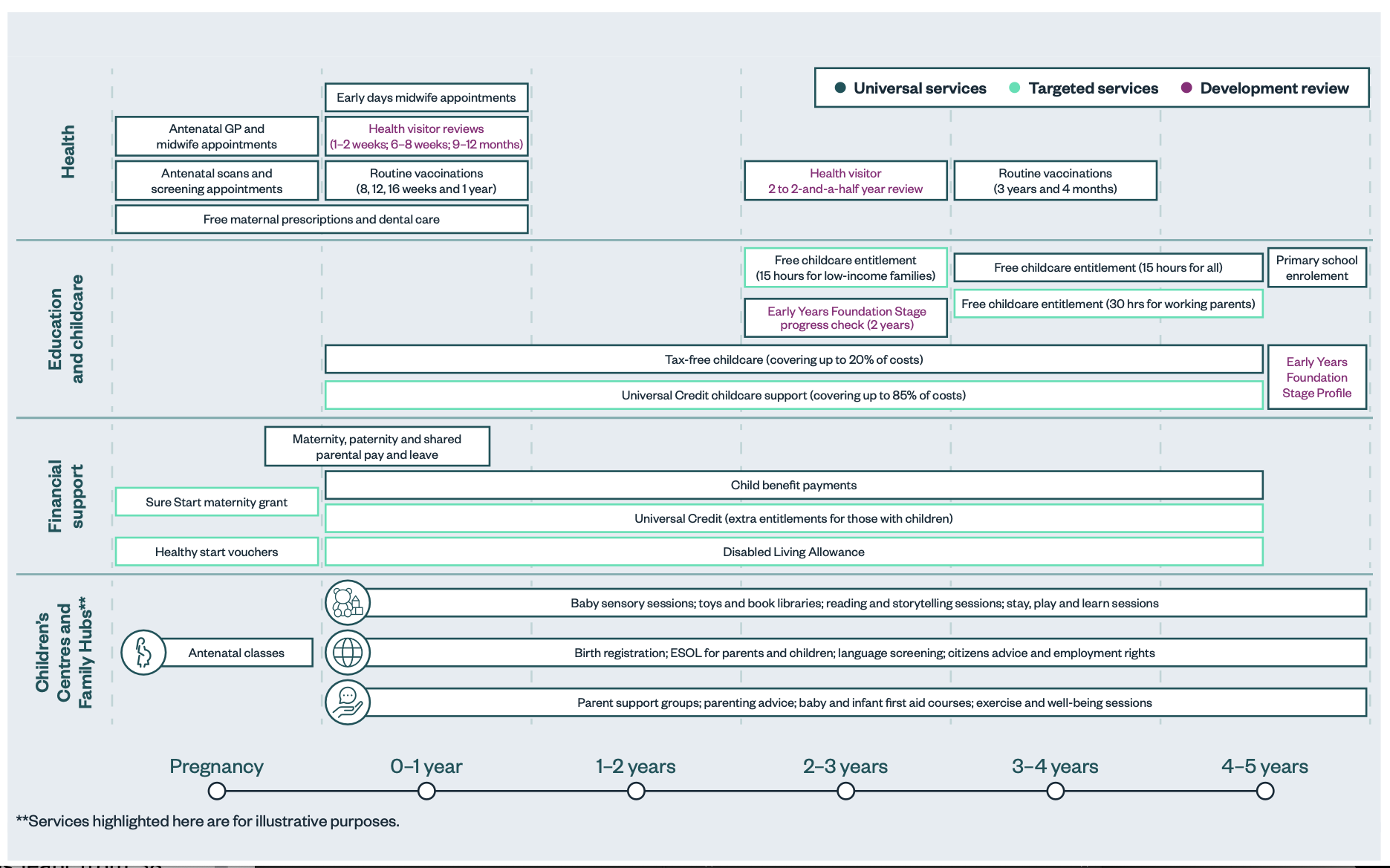

There is currently a myriad of services available to families with young children, fragmented between education and childcare, health, social care, financial support and housing, and between parents and children.

We are still living with the legacy of major reductions in public spending on financial support for young children and preventative local services during the years of austerity. This has left some families particularly exposed to the economy and health shocks of the Covid-19 and cost-of-living crises. In terms of services offered, there remains a significant gap in state support for parents between the end of paid leave after nine months and the beginning of free childcare entitlements at age two or three.

‘Universal and targeted early childhood services in England’

Figures: Nuffield Foundation

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Virtually all children experience some form of state-financed formal early education and childcare before they start primary school. In 2022, 92 per cent of three- and four-year-olds took up the universal entitlement to 15 hours of term-time state-funded early education.

Over the past 20 years, there has been a particularly big rise in the number of three-year-olds taking up the 15 hours entitlement (from 71 per cent to 87 per cent). However, access to early education is not yet universal and the most disadvantaged families are less likely to access their free entitlement. In 2022, 28 per cent of disadvantaged two-year-olds are missing out, and in the previous year it was as many as 38 per cent.

At its best, the early entitlements are transformative for both children and their families. Yet as many as two in five children are not reaching their expected levels of development by the start of primary school. As well as problems with the overall quality of provision for children, our dysfunctional system doesn't work for anyone – for parents in terms of access and affordability, for the workforce on pay and training, or for providers on sustainability.

Rising rates of early childhood poverty have also been a long-standing feature of the early years landscape, and since 2013/14, these rates have risen even more, largely as a result of benefit changes, in particular the two-child limit under Universal Credit. Just over half of families with three or more children, where the youngest child is under five, are now living in poverty.

Since 2013/14, rates of poverty for families in part-time work with at least one child under five has leapt from 38 per cent to 64 per cent – now the majority of parents in this category, and almost the same level as for children whose parents are unemployed.

The rate of poverty is also increasing for children with at least one parent in full-time work, from 19 per cent in 2013/14 to 25 per cent in 2019/20.

The burden of poverty still falls hard on ethnic minorities. Almost three in four (71 per cent) of children in families where the youngest child is under five from Bangladeshi backgrounds live in poverty, and in several other minority ethnic groups, more than 50 per cent of families are living in poverty. These higher rates of poverty partly reflect the younger age profile of ethnic minority groups but also structural inequalities and discrimination, including higher unemployment and lower earnings.

WHERE ARE WE GOING?

Despite the importance of the first five years of a child's life, public policy continues to focus on school-age children, above babies and young children.

In England, the need for better-co-ordinated services has started to be recognised through The Best Start for Life initiative and the expansion of Family Hubs.

The Best Start for Life has brought the period from pregnancy to age two into focus and has opened up the possibility of a more ambitious, integrated approach to early childhood. In the medium term, The Best Start for Life's vision needs to be extended up to the age of five and connect across all services for families, including efforts to tackle poverty.

In April 2022, the Government announced £300 million of funding for 75 local authorities to create Family Hubs and early help services over the next three years, jointly overseen by the Department for Health and Social Care and the Department for Education. While welcome, this investment follows years of funding reductions for Children's Centres and will benefit just half of England's local authorities.

While the pandemic created huge pressures for these services, it also catalysed innovative practice, working across boundaries, the use of technology to work with families in new ways and the creation of more parent-led groups. Although temporary, the £20 uplift in Universal Credit demonstrated that changes to benefit payments can have an immediate impact on alleviating poverty.

There is a long-standing body of international evidence which shows that high-quality pre-school provision can have positive impacts on young children's development, while more recent research shows that some of these effects fade out in primary school. But the effects of the Covid pandemic lockdowns and wider pressures have also given us insight into what happens when children are not able to go to nursery or childminders – with marked falls in their development especially in relation to communication and language, and not being ready to start school.

The research shows that free childcare has had some limited impact on maternal employment, particularly for lone parents. The expansion of free entitlements and greater flexibility has made childcare more affordable for many families. Evidence-based programmes, such as Incredible Years and the Nuffield Early Language Intervention, have been shown to be effective.

Sure Start Children's Centres had mixed results initially, but by 2010 had shown impact on the health of young children and in the home learning environment. A more recent study has shown that Sure Start led to a significant reduction in hospitalisations among children by the end of primary school in disadvantaged areas.

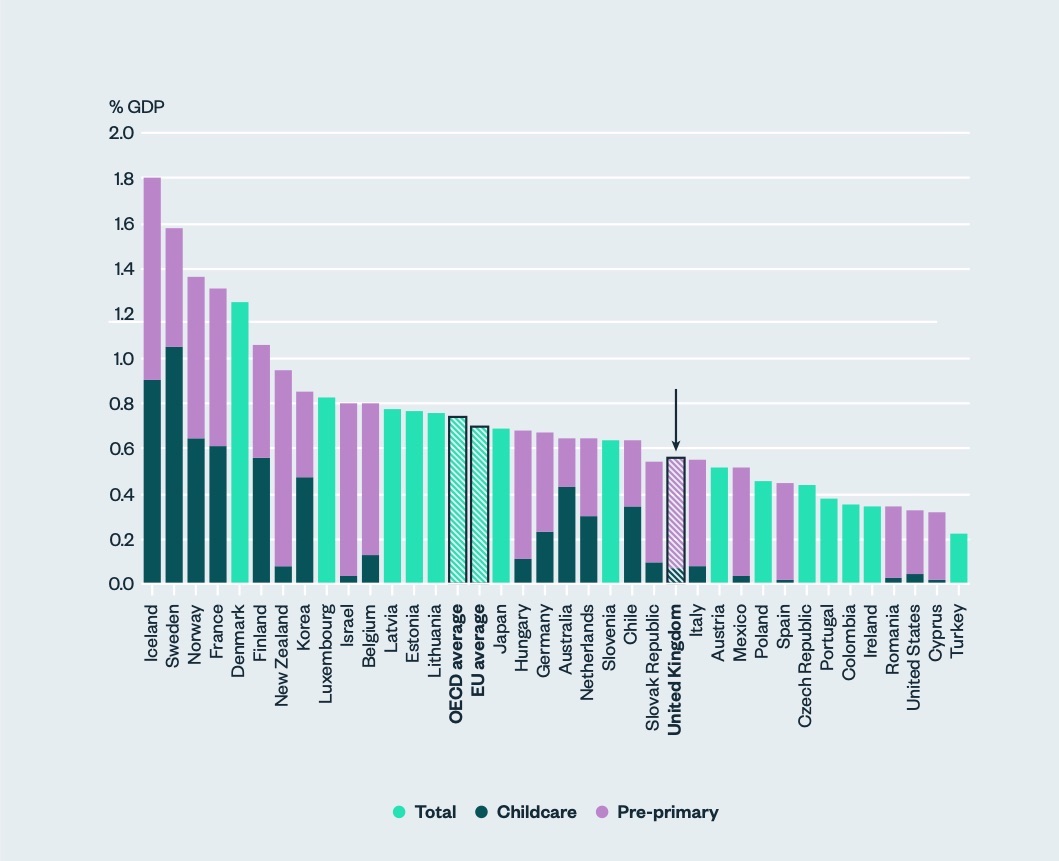

Despite this evidence, the UK's investment in early education and childcare as a proportion of GDP falls well below the OECD average.

Early years and childcare services have great potential to make a positive difference to young children's lives now and in the future if they have the right investment, reform and greater integration.

'Public expenditure on childcare and pre-primary education and total public expenditure on early childhood education and care, as a percentage of GDP, 2017 or latest available’ (Note: Countries for which only a total proportion is included are those for which data cannot be disaggregated by educational level. Data may not fully capture all local government expenditure data in all countries. The EU average includes UK data)

'Public expenditure on childcare and pre-primary education and total public expenditure on early childhood education and care, as a percentage of GDP, 2017 or latest available’ (Note: Countries for which only a total proportion is included are those for which data cannot be disaggregated by educational level. Data may not fully capture all local government expenditure data in all countries. The EU average includes UK data)

This article is based on the Nuffield Foundation's 'The changing face of Early Childhood' series, which brings together the research and evidence on early childhood in the UK and presents recommendations for policy and practice

Download 'The Changing Face of Childhood in the UK' here