Ladybird has been producing familiar and much-loved children’s books for many decades, and most recently it has become best known for its novelty titles such as The Mid-Life Crisis, Dating and The Ex. However, in the early 1960s, Ladybird was well-known for a different trend: it took the decision to print many of its titles using ‘ita’ – the Initial Teaching Alphabet.

Ita was a device introduced into many British schools in 1961, later spreading to the USA and Australia. It was, essentially, a variant on the alphabet created with the intention of helping English-speaking children to learn to read easily and quickly. Interestingly, ita was the invention of Sir James Pitman, grandson of Sir Isaac Pitman who invented Pitman’s shorthand – another man ostensibly concerned with speed.

Ita was a device introduced into many British schools in 1961, later spreading to the USA and Australia. It was, essentially, a variant on the alphabet created with the intention of helping English-speaking children to learn to read easily and quickly. Interestingly, ita was the invention of Sir James Pitman, grandson of Sir Isaac Pitman who invented Pitman’s shorthand – another man ostensibly concerned with speed.

As might be expected, opinions regarding the efficacy of the approach varied: it is perhaps indicative that it never went mainstream and was not rolled out nationally. By the mid-1970s it fell into disuse and such versions of the Ladybird books disappeared off the radar.

PRINCIPAL FEATURES

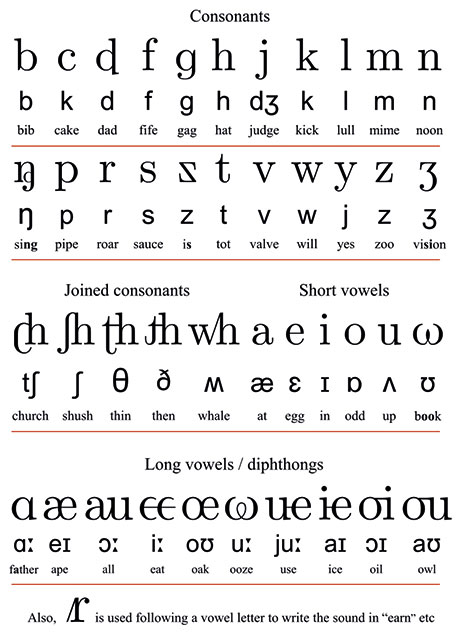

Ita consisted of 44 characters: some of them being the standard Latin letters and the others created specifically for this new alphabet. Each character of the ita alphabet had a name and represented a single sound or phoneme.

A special typeface was created for ita and, notably, all characters were lower case. If a capital letter was needed it was denoted, perhaps logically, by using a larger version of the lower-case letter.

The fundamental aim of the approach was that children would learn to read and spell using this preliminary alphabet and, when fully conversant with it (usually around the age of seven), would move on to the standard English orthography. Ita was not intended to replace the conventional alphabet but to be used as a precursor to it.

PRINCIPAL PROBLEMS

Though the intention of ita was to create a simplified version of the written word, making it easier and quicker for the child to read, it turned out in many ways to be the very opposite. Ita, in fact, added several complications to learning to read:

Ita words were not seen in the environment – they were not written on food packets, on children’s games, in shops, on TV and so on. This is perhaps an obvious hindrance regarding learning to read. Children rarely learn to read exclusively from the text in books. Rather, for many children their main (and sometimes only) interest in reading is that it is purposeful – words need to have meaning in their day-to-day lives. This, of course, could not be the case with a made-up alphabet – road signs were not written in it, nor were the words on cereal packets, or in birthday cards or, indeed, children’s own names.

Dealing with two alphabets for the same language is a tall order and potentially confusing for any of us, let alone for a young child in the very early stages of reading.

Making the transition from using ita reading skills to reading the standard English alphabet is something of a challenge. Learning to read text using one set of tools and rules, and then having to un-learn these in order to read using both a different script and a new set of tools, often proved too demanding for children.

Being substantially phonetic, ita did not account for regional differences in accent. Several words that read phonetically in London did not in Yorkshire.

An independent study by Warburton and Southgate (1966) found that the children who experienced an early advantage through using ita did not gain from this beyond the age of eight.

When the BBC surveyed those who had learnt to read using this system in 2005, the majority said they felt that it had hampered their reading and spelling (Eye magazine, issue 55, spring 2005).

CONTINUING CONTROVERSY: PHONICS AND DECODING

Ita was certainly a controversial educational typographical experiment that, arguably, both children and their parents were subjected to without any real choice. In common with much current practice it was, at heart, an approach to the teaching of reading with phonics as its central feature.

Such approaches are based on an understanding that reading is principally about being able to say the sounds represented by marks on a page. Frank Smith, one of the originators of the modern psycholinguistic approach to reading instruction, would not refer to this skill as reading, but decoding.

The Key Stage 1 phonics screening prioritises this very skill. Children are expected to read words or, more accurately, non-words, such as ‘vap’, ‘blard’, ‘coid’, ‘dat’, ‘glog’. The sole expectation is that children should be able to articulate sounds and to blend them.

It is rather like when we try to ‘read’ a foreign language simply by decoding it – it means absolutely nothing to us, it is just a series of enunciations.

On holiday in Greece, a friend of Greek origin said, ‘I can read Greek, but don’t understand what it means’ – she could decode the letters on the pages using the correct pronunciations, but she did not have a clue what they actually meant. This ‘reading’ was certainly of no use in getting us around Greece!

NOT ALL NONSENSE

There is, however, is a category of non-standard or made-up words that do hold a valuable place in literature. Dr Seuss’s There’s a Wocket in my Pocket!, for instance, provides us with a whole host of these: a yottle in the bottle, a zable on the table, a zlock behind the clock, that bofa on the sofa, and a zamp in the lamp.

There is, however, is a category of non-standard or made-up words that do hold a valuable place in literature. Dr Seuss’s There’s a Wocket in my Pocket!, for instance, provides us with a whole host of these: a yottle in the bottle, a zable on the table, a zlock behind the clock, that bofa on the sofa, and a zamp in the lamp.

Though they are all made-up words not found in the dictionary, they are all words which, in their context, have meaning ascribed to them – in the book they work as proper words. We might refer to them as ‘nonsense’ words, yet they are not nonsensical.

On the contrary, the made-up words that young children encounter today in the Year 1 phonics screening test are a far cry from this and bear little resemblance to this creative, playful way with language. Isolated strings of letters on a page are of an entirely different calibre: there is very little, if any, overlap between these and Dr Seuss’s ridiculous rhymes.

On a similar note, the relatively recent new words – lol, btw, imho – may appear as strings of letters or non-words but are initialisms (like the ‘BBC’) and are heavily embedded in meaning.

LIFE-LONG PLEASURE?

Reading is, for many, a cherished, enriching and life-long pleasure. The teaching of it should be handled with great care. Being offered the opportunity to cultivate a love of reading is a most valuable gift. It is not, however, by any means a straightforward matter: one size does not fit all. The mainstream view, though, would be that phonics first is the ‘one size that fits all’. You could comment that while there is evidence that children are better readers, as such, there also seems to be sound evidence that they aren’t actually reading as much as they used to.

Creating systemised shortcuts and getting quick results was tempting when ita was developed in the 1960s, and it is just as tempting these days. But it is unforgivable if it is of detriment to the young reader and, indeed, the future reader (perhaps, even, non-reader).

Clearly, and thankfully for most, ita fell out of fashion and became defunct after a relatively short time: lessons were learnt by educationalists. But if we really are facing a serious decline in children’s reading year on year, will we soon be concluding that the ‘one size fits all’ early formal teaching of reading, with its overuse of phonics and the lack of emphasis on a multitude of strategies, is not working in England? The great cost to the reader is the loss of a true and life-long enjoyment of books.