bilingual children. Professor Elena Lieven explains.

Across the world, children learn very different languages in very different child-rearing situations and cultures. So, what does this tell us about the development of language and communication? And how might these differences affect a child's ability to settle into nursery?

LANGUAGE DIFFERENCES

Languages differ in both their structure and what you can and can't express in a given language. English speakers tend to assume that English 'ways' are 'natural' and common to all languages 1. But languages differ in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways, and early years practitioners need to take account of these differences when working with bilingual children. Here are some examples.

Word order and shape

In English it really matters whether you say 'Man eats dog' or 'Dog eats man'. But many other languages, such as Polish, change the shape of the words (in this instance, 'dog' and 'man'), rather than the word order, to indicate who is eating and who is being eaten. It also means that the speaker doesn't have to stick to one word order.

Changing word shapes to change meaning (called 'inflection') is very common across the languages of the world. A simple example from English is the way we add 's' to mark plurals (for example, one dog, two dogs) or change 'he' to 'him' depending on whether the person 'is doing' or 'being done to' (for example, 'He hit him').

Practice point: Nursery children whose first language has many inflections might struggle to grasp the importance of word order in English.

Omitting words

In some languages, including Chinese, the speaker can leave out who is involved in an action. So, if a person hears 'dog eat' in Chinese, they have to work out from the context whether the dog is eating or being eaten.

Practice point: Such omissions are quite typical in early English language development, but might last longer in children whose home language doesn't require full sentences.

Meanings

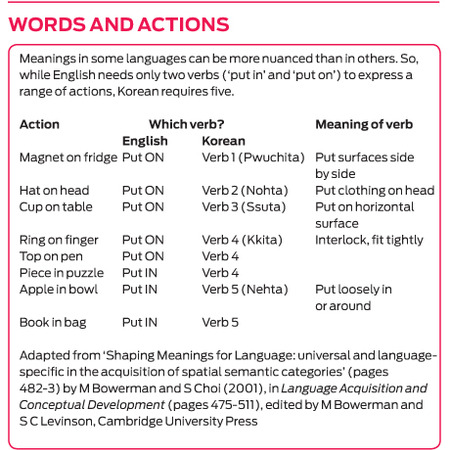

Some languages include concepts or make distinctions that may differ, or not even exist, in other languages. For example, in English, we use 'in' for pretty much any situation where one thing is inside another. But in Kor- ean, it matters whether the object fits tightly (for example, a hand in a glove or a ring on a finger) or loosely (for example, an apple in a bowl) and there are two words for these two situations - so the meanings cut across our English meanings of 'in' and 'on' 2 (see box below).

Another example is the verb 'to eat'. While in English it is used for almost any food we consume, in the Mayan languages of Mexico, the general word for eating is rarely used. Instead, a variety of verbs are used depending on what a person is eating, such as tortillas, crunchy foods or fruit 3.

Practice point: A bilingual nursery child may make seemingly strange errors in English, when, in fact, they are simply getting to grips with how English divides up meaning compared to their mother tongue 4.

Politeness

As we have seen, there are instances when it is possible to omit some words in some languages. However, there are also occasions when it is imperative to include certain words, and this is particularly true when it comes to politeness.

All languages have quite strict rules about how to address, or refer, to people. An example, in English, is the difference between using 'Mr/Mrs', first names, or 'auntie/uncle'. In some languages, including Korean and Japanese, a variety of words have to change, depending on whether you are talking to, or about, someone of higher status than yourself. So, how you address your grandparents may be different from how your parents address them or how they address you. Children learn the basics of address within these languages at a very early age because it is so central to social interaction in these cultures.

Practice point: These children may be confused about polite forms of address when learning English, causing them to be shy when speaking to or attracting the attention of teachers 5.

EARLY COMMUNICATION: BIOLOGY AND CULTURE

However complicated other languages may appear to us, children seem to be on a roughly similar timetable for beginning to understand their first language and for developing some of the early interactive skills that support this understanding.

For instance, studies in Peru, Canada and India asked parents at what ages their children understood ten words - all groups reported this to occur at about nine to ten months. And children started to point for others, to imitate, to initiate interactions and to help co-operatively at very similar ages across different cultures and across rural and urban, non-industrialised and highly educated, social groups 6, 7, 8.

Studies have found that there are some basic ways in which caregivers interact with babies and infants in all cultures:

- body contact (in many cultures babies are carried until they can sit/walk)

- body stimulation (tickling/stroking)

- object stimulation (attracting the baby's attention with objects), and

- face-to-face (holding the baby up in front of the caregiver's face and exchanging smiles/vocalisations 9, 10).

But the relative amount of these activities varies between cultures. Does this mean that how people interact with infants doesn't affect their language development? The answer is 'yes' and 'no'. Of course, there are major individual differences between typically developing children within a culture which affect how fast they learn to talk (see part 1 in this series, 'Up to speed?', at www.nurseryworld.co.uk), but studies show a very similar average onset for these communication skills across different cultures.

This probably means that there is some sort of biological timetable for these early communication skills to emerge. But it doesn't mean that this is inevitable, nor that it will happen without the basic nurturing and interactive environment that characterises normal care of infants the world over.

Practice point: When trying to establish whether a child from another culture has delayed language development, check for early interactional skills. For instance, if a child in a baby room doesn't point, imitate, or initiate interactions or help at the same age as monolingual English-speaking children, then this should be taken as a possible sign of delay and tracked.

Sharing activities

While the age at which children start to produce these skills may vary little on average, how much they go on to use them is affected by the culture in which they are growing up. Cultures vary enormously in how often carers share each of these activities with their babies - and also whether one or two caregivers or a much wider group of adults and children is involved with the child.

For example, how much adults imitate children may not affect when children themselves begin to imitate, but it does affect how much they do it 11. And while beginning to understand language seems to start about the same time, the age at which children start to produce language varies.

Middle-class children growing up in Canada produce their first ten words three months earlier than children growing up in rural Peru and India 6. This is almost certainly due to cultural differences in the amount of talk directed to babies. So, on the one hand, babies do seem to be on some biological timetable for these early communicative behaviours but, on the other, their cultural environments differ very widely and this has important influences on aspects of child-rearing and children's development.

CHILD-REARING AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

As we know, there are big differences in our own culture in how much parents talk to children, and this is clearly related to children's own language development and school readiness (see earlier articles in this series - 'Up to speed?' 'Word for Word' and 'A Formal Occasion?' - at www.nurseryworld.co.uk).

These differences may come partly from different views of how children should be brought up and their place in family and culture. An awareness of how cultural practices and beliefs differ can help practitioners to engage effectively with caregivers and children and overcome any feelings that the family may have of being 'outside' the culture of the nursery.

Here are some examples of these cultural differences:

- In one community in the southern USA, people took the view that children had to learn for themselves and that there was no point trying to teach them things like language 12. To be heard, young children had to break into conversations between adults to attract their attention and to do this, they would start by imitating the ends of utterances in the adults' conversations (see case study).

- A very different attitude is reported for a highlands culture in Papua New Guinea, where parents said that children had to be drawn away from their baby chatter and into the adult culture by being taught to speak. So, adults spent a lot of time teaching children exactly what to say in particular situations 13.

- Differently again, in Samoa, child-directed speech, so typical of our own middle-class communities, would be thought very odd indeed, as in this culture conversations are governed by status - people of lower status must adapt to those of higher status and children are, by definition, of lower status than adults 14. So adults tend to tell older children what to say to younger children and certainly don't adjust their speech when talking to very young children.

- Finally, in the Mayan cultures of the Mexican Chiapas, studies report that there is a strong emphasis on not over-exciting babies who are thought to be very vulnerable. This results in babies being raised without a great deal of infant-directed speech or interaction 15.

Practice point: Given these cultural differences, it is easy to see why some parents and caregivers may feel confused by nursery practitioners' advice on how to promote children's language development. If parents come from a culture where language is taught explicitly, they may be bewildered by practitioners' advice not to correct children's language mistakes. Conversely, if the parent culture does not promote early language, they may fail to see the point of advice to repeat and expand upon their children's utterances.

Comparing cultures

Most of these studies were carried out by anthropologists who lived in these communities for considerable lengths of time. But another approach to understanding child-rearing traditions and their impact on language development is to develop measures to compare across cultures.

One such measure is a dimension of interdependence or independence. In interdependent cultures, the emphasis is on the child's membership of a community: babies never sleep alone, they are breastfed on demand, with almost continuous bodily contact, but they are talked to less and parents are concerned with politeness and the child's membership of the social group.

At the other end of the continuum, in independent cultures, parents' emphasis is on the child as an autonomous agent, treated as an independent person from the outset and talked to much more often, but also spending more time sleeping and playing alone 9.

This is often seen as a dimension with rural, non-industrial cultures on the interdependent end and urban, advanced industrialised cultures at the independent end. While this continuum does seem to capture some of the realities of child-rearing in these societies, it is important to avoid any oversimplification and recognise the variations within it. For example, in comparing two highly industrialised societies, researchers have placed Japanese child-rearing on the interdependent end and the USA on the independent end 16.

Practice points: Early years practitioners should avoid making assumptions about:

- the amount of talk to children within families, as there can be major differences between two traditional societies or between the subcultures of modern industrial societies

- one-to-one interaction with one primary caregiver - some babies will have a range of caregivers, including quite young children; even before they can walk or talk, babies will often be carried around by older children, and once they are a bit older may spend most of their days running round in groups with other children.

LEARNING TO TALK: DIFFERENT STRATEGIES

All these differences in languages and child-reading practices suggest that children in different communities may have to use rather different strategies in discovering how their language works 17:

Observation

Some children may have to learn more from observation than interaction with adults, and from listening to others rather than being addressed directly by adults who adapt their every word to the attention and interests of the child.

For example, a study in Mozambique of pre-verbal infants' attention found that babies in the more rural group spent much more time watching their caregivers closely as they worked and talked. This differed from the group living in a nearby town, where mothers and pre-verbal infants jointly spent more time in attending to objects and playing with them 18.

In another study of rural and urban children in Mexico, researchers taught one child how to make a toy, while a second child was given a different task. When they tested the second children the following week, the rural ones had learned to do the task by observing, while the urban ones had not 19.

There is only limited research into how children learn from observation, but these studies do suggest that some children learn by observing silently what is going on, rather than always engaging directly in conversation with other children and adults.

Practice point: Don't assume that a child who is observing quietly on the sidelines is not learning.

Imitation

Imitation is another strategy that can be very useful in language learning. Learning to talk means breaking up what you hear and working out which bits go with which meaning. Imitating the ends of adult utterances is a good way to learn to pronounce words and sentences.

As we have seen, in some cultures adults encourage this by teaching the child to imitate. In others, children do it for themselves by imitating adult conversation. Either way, it gives the child a handle on starting to talk.

Once they can imitate, they start to play with these imitations, adding words and elaborating what they have learned. Studies of children talking to themselves when they are on their own give a good idea of how creative this imitative talk can be 20, 21.

Practice point: Although the automatic repetition of other people's utterances is often associated with a diagnosis of early autism, it could equally reflect a pattern of talk between adults and children in some cultures. To establish whether there is a problem, early years practition- ers should check whether the child fairly quickly starts to play with the language and add words to their imitations 22.

CONCLUSIONS

Many of the languages and cultures discussed here may seem far removed from our own, but what they tell us about language development is hig- hly relevant when caring for young children from different backgrounds.

- Features of a child's mother tongue may create particular hurdles for a child as they learn English, and early years practitioners need to be aware of this.

- Attitudes to raising children, what they need to be taught and how they learn language may differ and affect the ways in which a child can cope with the nursery environment. This also applies to children of different British subcultures.

- Children raised in big family groups, and spending more time with other children rather than in one-to-one interaction with a single primary caregiver, may have developed very different strategies of attention and observation.

These are just some elements of a family culture that practitioners might seek to understand and accommodate within their early years settings - having some understanding of a family's language and child-rearing traditions can only benefit early years practice.

Professor Elena Lieven is based in the Child Study Centre at the University of Manchester and is the director of the ESRC International Centre for Language and Communicative Development (LuCiD). Find out more about LuCiD's work at www.lucid.ac.uk

CASE STUDY: WHO'S TALKING?

One community in the southern USA did not teach their children to speak, believing that children had to learn for themselves. To be heard, young children had to break into adult conversations by imitating the ends of adults' utterances, as in this conversation involving Lem (16 months old), her mother Lillie Mae and another adult, Dovie Lou:

Liilie Mae: And she's been going down there about every week, but I don't believe they've got no jobs.

Lem: Got no jobs.

Dovie Lou: That woman down that employment office don't know what's going on, she send Emma up there to the Holiday Inn two times and they ain't had no job.

Lem: No job.

Lillie Mae: She think she be helping.

Lem: Be helping.

Adapted from Ways with Words (page 91) by S B Heath (1983), Cambridge University Press.

REFERENCES

References

- Deutscher, Guy (2005). The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind's Greatest Invention. William Heinemann (UK).

- Bowerman, M and Choi, S (2001). Shaping meanings for language: universal and language-specific in the acquisition of spatial semantic categories. In M Bowerman and SC Levinson (Eds) Language acquisition and conceptual development, (pp475-511). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, P (1998). Children's first verbs in Tzeltal: Evidence for an early verb category. Linguistics, 36(4), 713-753.

- Evans, Nicholas (2010). Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Brown, P (2011). Politeness. In PC Hogan (Ed), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the Language Sciences (pp635-636). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Callaghan, T, Moll, H, Rakoczy, H, Warneken, F, Liszkowski, U, Behne, T and Tomasello, M (2011). Early social cognition in three cultural contexts. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 76(2): 1-142.

- Brown, Penelope (2011). The Cultural Organization of Attention in Alessandro Duranti, Elinor Ochs and Bambi B Schieffelin (Eds) The Handbook of Language Socialization. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lieven, E & Stoll, S (2009). Language development. In M Bornstein (Ed) The Handbook of Cross-Cultural Developmental Science, (pp143-160). New York: Psychology Press.

- Keller, H (2007). Cultures of Infancy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Bornstein, Marc, Putnick, Diane, Cote, Linda, Haynes, Maurice, O & Suwalsky, Joan (2015). Mother-infant contingent vocalisations in 11 countries. Psychological Science OnlineFirst.

- Liszkowski ,U, Brown, P, Callaghan, T, Takada, A and de Vos, C (2012). A prelinguistic gestural universal of human communication.Cognitive Science, 36, 698-713.

- Heath, SB (1983). Ways with Words. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Schieffelin, B (1985). The acquisition of Kaluli. In DI Slobin (Ed) The Crosslinguistic Study of Lanaguage Acquisition, vol. 1, ed, (pp525-593). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ochs, E (1982). Talking to children in Western Samoa. Language in Society,11, 77-104.

- Gaskins, Suzanne (2006). Cultural perspectives on infant-caregiver interaction. In NJ Enfield and Stephen Levinson (Eds) Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition and Interaction, (pp279-298). Berg: London.

- Murase, Toshiki, Dale, Philip, Ogura, Tamiko, Yamashota, Yukie & Mahieu, Aki (2005). Mother-child conversation during joint picture book reading in Japan and the USA. First Language, 25 (2), 197-218.

- Lieven, Elena (1994). Crosslinguistic and crosscultural aspects of language addressed to children. In C Gallaway and BJ Richards (Eds) Input and Interaction in Language Acquisition,(pp. 56-73). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mastin, J Douglas & Vogt, Paul (2015). Infant engagement and early vocabulary development: a naturalistic observation study of Mozambican infants from 1;1 to 2;1. Journal of Child Language, available on CJO2015. doi:10.1017/S0305000915000148.

- Rogoff, B, Correa-Chavez, M, & Silva, KG (2011). Cultural variation in children's attention and learning. In MA Gernsbaber, RW Pew, LM Hough & JR Pomerantz (Eds), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 154-163). New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

- Weir RH (1962). Language in the Crib. University of Michigan; Edition 2, (1970) Mouton.

- Nelson K, Oster E and Bruner JS (Eds)(1989). Narratives from the crib. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press.

- Fillmore, LW (1979). Individual differences in second language acquisition. In Charles J Fillmore (Ed) Individual differences in language ability and language behavior, (pp203-228). New York: Academic Press.