'formal' language. In the third part of our series on communication, Dr

Anna Theakston explains what it is and how to support it.

So much changes for children when they take their first step through the door of Reception at four years of age - their routines, their learning environment, even their clothes ... and the style of language that they are exposed to.

While home, and often nursery, uses mainly informal or 'conversational' language, in Reception children will hear much more formal speech - the kind of language that they will need for academic success. Reception class teachers need to be aware of the differences between these two styles, and the extent to which some newcomers to their class may struggle with the shift in language.

Nurseries and pre-schools too need to recognise their key role in easing this transition by providing children with opportunities to experience and develop their language skills, in particular this formal, or 'academic', style of speaking.

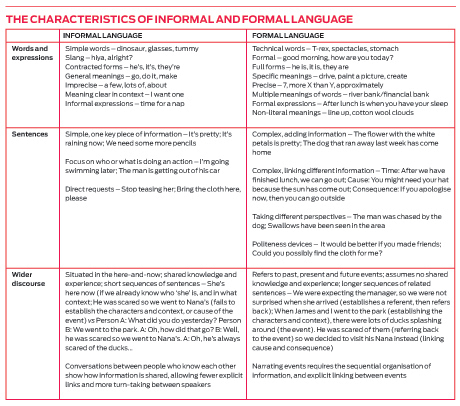

The three main characteristics that distinguish these two styles of language are their vocabulary, sentence structures and wider discourse1 (that is, how sentences are linked), and here we look at each.

DIFFERENT KINDS OF WORDS

Compared to conversational language, the vocabulary of formal language is more detailed and specific. To succeed, children need to know lots of different words and the sometimes subtle differences in meaning between them. For example, in conversation, we might say 'Let's go to the shops', but this leaves many options open - will we walk, stroll, drive, or cycle to get there? Being precise about meaning can help children to convey their messages more effectively.

Similarly, compare 'Did you miss me?' (as Dad collects his child from nursery) to 'Did you miss one?' (when the child is tidying up some crayons from the floor). Here, the word 'miss' means different things according to where and how it is used. Children need to learn what words mean in enough detail so they can get the right meaning in the right context.

Formal language can also contain expressions that don't mean quite what they say. How should the child interpret instructions like 'Line up!', or 'Cross your legs and fold your arms!' if the meaning has little to do with their experience of drawing lines or crossing the road? As children get older, knowing lots of words and their meanings can help them to understand more complex, non-lite- ral language such as metaphors (for example, 'Our cat is a tiger!').

Evidence shows that children begin to learn a more formal vocabulary when they hear lots of different words used in meaningful contexts2 (see part 2 of this series, 'Word for word', on word learning, 27 July-9 August).

At the beginning, repeating the same words is important to help children remember them. But over time, children need to hear lots of different words, not just the same words over and over again. Meaningful contexts are simply situations where children can work out what a new word refers to. For example, paying attention to what children already know and adding new words can help build vocabulary (for example, 'Wow, your tower looks like a skyscraper. A skyscraper is a really tall tower').

Further research suggests that children will learn word meanings best if they hear those words used in lots of different situations3. Pointing out a picture of a skyscraper in a book or on a computer and reminding children about their tower building activity can help them to remember the new word and its meaning. And although some carers worry about using 'big' words with young children, one study showed that if parents use the grown-up names for objects, concepts and events with their two-year-olds, by the age of three those children have larger vocabularies than children who hear less varied input4.

DIFFERENT KINDS OF SENTENCES

The formal language that children hear in the classroom contains longer, more complex sentences than they may be used to hearing in day-to-day conversation. Simple sentences including just one piece of information (for example, 'Put your coat on') are typical of informal conversation, whereas formal language contains sentences that combine more than one idea (for example, 'Put your coat on before you go out to play').

Complex sentences can include multiple instructions or a detailed description of something or someone. Often they link different parts of an event together by giving information about the order things happen (for example - before, after, when), or explaining the relation between cause and effect (for example - because, so, if, then).

In formal speech, even simple events can be presented in different ways by changing what part of an event is being emphasised (compare 'The zoo-keeper saw the tigers earlier' where the focus is on who saw the tigers, to 'The tigers were seen earlier', where the focus is on what was seen). And simple requests about behaviour may be framed less directly (compare 'Don't do that!' to 'I'd prefer it if you could find something else to do').

Research suggests that there are ways to help children understand and produce the kinds of sentences nee- ded for formal language. In one study, researchers looked at how often four-year-olds used complex sentences such as, 'We need an umbrella because it's raining', compared to simpler kinds of sentences.

Although some children's language contained a much smaller proportion of complex sentences than others, the researchers showed that when adults (either parents or teachers) talked to children using complex sentences this increased how often children produced these sentences, and how well they understood them5.

We also know that the order of information in complex sentences is important. When the language matches the order of events in the real world, this makes it easier for children to understand (for example, 'You can play before you have lunch'). But when language conflicts with the actual order of events, children can become confused about what to do first (for example, try changing 'You can play after you have lunch' to 'After you have lunch, you can play')6.

Sharing books with children can also help. Researchers have found that the text in children's books is often more complex than the daily language spoken to young children, so reading books can increase the amount of complex language children hear7.

Interestingly, different kinds of play situations also seem to promote different amounts of complex language at different ages. In one study, researchers found that two-year-olds produced complex sentences in free play and in structured play where they could manipulate toys and objects (for example, playing with a doll's house or pretending to visit the doctor), where as four-year-olds could manage the demands of retelling a familiar story (for example, Goldilocks and the Three Bears) and used complex language without actually acting out the events8. Role play with young children is beneficial because it introduces them to new words in a familiar context and can help them to describe a sequence of events using complex sentences.

Another source of information children might use to help them with complex sentences is the hand gestures we produce when we speak (for example - pointing, using the hands to indicate the shape or size of something, or its location; try watching someone speaking to see what their hands tell you).

One study showed that three and four-year-olds could understand complex instructions better (for example, 'Find the block that has an arrow pointing up and a smiley face with a rectangle above it') if simple finger points (up) and the positioning of the hands (one fist above the other) were used to illustrate the meaning9.

Another study found that children understood complex sentences better (for example, 'It was the dog that the cat chased') if simple hand movements were used at the same time that the two participants were mentioned10. Although there are large differences between people in how often they gesture when speaking, encouraging children to look at the speaker while listening, rather than looking away, could help them to pick up important information.

THE WIDER DISCOURSE - LINKING SENTENCES

In most everyday conversations, the speaker and listener share some knowledge and experience, so it is unnecessary to explain everything in detail.

In most everyday conversations, the speaker and listener share some knowledge and experience, so it is unnecessary to explain everything in detail.

In a formal language context, on the other hand, the speaker has to set up the situation or event, explain new information, and link everything together to form a coherent story or argument. This is why formal language is essential for all academic subjects; it is used for organising information, solving problems, and exploring the causes and consequences of events11.

However, formal language is important for more than academic success. These same language skills help children to build successful social relationships through discussion and negotiation with other children. As there is evidence of an association between poor language skills, poor social skills and anti-social behaviour, there is good reason to focus on children's early exposure to formal language 12,13.

Researchers have identified strategies to help children think about events in ways that support formal language. For example, asking children to tell stories or recall past events helps them to organise information. They need to describe the setting, introduce the characters and explain the sequence of events14.

Although it takes children many years to become good storytellers, caregivers can start the process by helping young children to see links between events. Open-ended questions encourage children to think about causes and consequences (for example, 'Where did he go?', 'When did you feel happy?', 'Why did that happen?'). When children are asked exactly these types of questions to help them recall past events, they can tell more complex stories a year earlier than children who were not given this help15.

In another study, researchers showed that when adults encouraged children to ask 'why' questions and use 'because' explanations, children began to use these kinds of complex sentences more often in their discussions with other children (for example, A: 'I've a broken spaceship.' B: 'Why did the spaceship crash?' A: 'Because he wasn't a very good driver.')16. This shows that children are able to learn from the examples adults provide and transfer this information to new situations.

Finally, one study found that if children could see the hand gestures adults use when telling stories, they were better at retelling the stories than children who could not see any gestures. This suggests that the hand gestures helped the children to remember more about how the different parts of the story fitted together17.

All these differences between the informal language of home and the formal language of education mean that children who enter school with poor language abilities and little prior experience with formal language have an increased risk of poor educational outcomes18. So learning environments that help children to become familiar with different kinds of formal language (see box) could give children an advantage right throughout their education.

TALKING TIPS

To help children become familiar with 'formal' language:

- Use lots of different words. Explain new words as part of the conversation.

- Use words in lots of different situations to help children work out their meanings.

- Use 'grown-up' words so children get used to them.

- Read books with children so they hear new words and sentences.

- Use a mixture of shorter and longer sentences, and think about different ways to say the same thing.

- Face children when you talk to them so they can see your hand gestures.

- Match the information in your sentences to the order that things happen in the world (do this then that; after this, do that).

- Ask lots of questions (what, where, why, how?) to help children to describe and explore causes and consequences.

- Talk to children about past events to help them recall and structure information.

- Ask children to retell stories to you.

- Give children time to respond. Remember, it can take a while to work out what to say.

References

1 Schleppegrell, M (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

2 Hart, B, & Risley, T (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

3 Perfetti, C (2007). Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading,11 (4), 357-383.

4 Rowe, M (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Development, 83(5), 1762-1774.

5 Huttenlocher, J, Vasilyeva, M, Cymerman, E, & Levine, S (2002). Language input at home and at school: Relation to child syntax. Cognitive Psychology, 45(3), 337–374.

6Clark, E (1971). On the acquisition of the meaning of before and after. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 10(3), 266-275.

7 Cameron-Faulkner, T & Noble, C (2013). A comparison of book text and child directed speech. First Language 33 (3), 268-279.

8 Klein, HB, Moses, N & Jean-Baptiste, R (2010). Influence of context on the production of complex sentences by typically developing children. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 289-302

9 McNeil, N, Alibali, M, & Evans, J (2000). The role of gesture in children’s comprehension of spoken language: now they need it, now they don’t. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 24, 131-150.

10 Theakston, A, Coates, A & Holler, J (2014). Handling agents and patients: Representational co-speech gestures help children comprehend complex syntactic constructions. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1973-1984.

11 Dockrell, J & Lindsay, G (1998) The ways in which speech and language difficulties impact on children’s access to the curriculum, Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 14, 117-133.

12 Palmer, E & Hollin, C (1999). Social competence and sociomoral reasoning in young offenders. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 79-87.

13 Snow, P & Powell, M (2005) What’s the story? An exploration of narrative language abilities in male juvenile offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 11 (3), 239-253.

14 Snow, C (1983). Literacy and language: Relationships during the preschool years. Harvard Educational Review, 53, 165–189.

15 McCabe, A, & Peterson, C (1991). Getting the story: A longitudinal study of parental styles in eliciting narratives and developing narrative skill. In A. McCabe & C. Peterson (Ed.), Developing narrative structure (pp. 217-253). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

16 McWilliam, D & Howe, C (2004). Enhancing preschooler’s reasoning skills: An intervention to optimise the use of justificatory speech acts during peer interaction. Language and Education, 18, 504-524.

17 Demir, O, Fisher, J, Goldin-Meadow, S & Levine, S (2014) Narrative processing in typically developing children and children with early unilateral brain injury: Seeing gestures matters. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 815-828.

18 Stothard, S, Snowling, M, Bishop, D, Chipchase, B & Kaplan, C (1998). Language-impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence, Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 41, 407-418.