Although as adults we assume labels such as mother, father, grandchild, friend, aunt or employee, these labels are not related to our intellectual ability. However, for children in education, even in early years, labels are used to categorise them according to their ability. Labels including ‘more able’, ‘gifted’, ‘high ability’, ‘under-achieving’, ‘not at the expected level’ and many other variations are commonplace in settings and schools. Not to mention Pupil Premium, Special Educational Needs and English as an Additional Language. This raises the question about the purpose of these labels and whom they are for.

The notion of labelling children using ability-focused language is in conflict with the whole essence of the ‘unique child’, which is embedded in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS). This statutory legislation acknowledges that all children develop at different rates, and it is our responsibility to ensure our practices and policies reflect this. To emphasise this, the Statutory framework states…

‘In planning and guiding what children learn, practitioners must reflect on the different rates at which children are developing and adjust their practice appropriately’ (DfE, 2023, p.16).

Similarly, under the grade descriptors for personal development, settings are expected to ensure that ‘children are gaining a good understanding of what makes them unique’ (DfE, 2019) in order to be graded ‘good’.

HOW HAS THE IDEA OF LABELLING EVOLVED?

Labelling children can relate back to the concept of the ‘ideal pupil’, a coin termed by Becker. This suggests that there are expectations of children to act a particular way, in line with middle-class notions in relation to behaviour, academic capabilities and language. There are also links to the idea of stereotyping in education, assuming that all children from a low socioeconomic background will be under-achieving and all those in lower-ability groups will be ‘badly behaved’.

Labelling children can relate back to the concept of the ‘ideal pupil’, a coin termed by Becker. This suggests that there are expectations of children to act a particular way, in line with middle-class notions in relation to behaviour, academic capabilities and language. There are also links to the idea of stereotyping in education, assuming that all children from a low socioeconomic background will be under-achieving and all those in lower-ability groups will be ‘badly behaved’.

However, this fails to recognise that all children have unique potential. Rather than assigning labels, instead we can celebrate children’s uniqueness. In doing so, we respect that children join a setting with varied prior experiences and knowledge.

A deficit approach would see us rush in with a catch-up narrative in order to plug the gaps. However, this assumes that the child is culturally disadvantaged, rather than acknowledging their unique traits. In turn, this questions what we value as a society and is the point where tensions between personal and professional ideologies arise.

Roberts-Holmes (2021) suggests that pedagogical practices in early years are influenced by a school readiness narrative which leads to pressure to nurture attainment. This can lead to labelling and grouping as a way of ensuring children make progress according to their perceived level of ability. Although grouping is more often associated with older children in primary schools, the concept has filtered down, leading to children being labelled for the purposes of data, even in nursery.

Bradbury (2018) considered the ability grouping of children in early years and how this has been exacerbated as a result of the phonics screening check which takes place when a child is in Year 1. The suggestion being that mixed ability groups are more challenging to teach and that children learn better when they are able to learn according to their level and pace.

This fits with the belief that ‘no one can fall behind’, leaving the option to differentiate by ability as way to address the issue. Segregating children in this way is said to reflect the ideologies of schools, based on our assumption of children being in education to achieve, linking to assessment and testing practices. Indeed, our assessment in early years can even be said to start with the progress check at age two.

However, labels suggest a limit to the capacity at which a child develops and learns and thereby achieves. The issue here is the assumption that all children have a predetermined intellectual capacity, taking us back to the nature versus nurture debate. In fact, a child’s intelligence is shaped by multiple factors. Children are influenced by their peers and, as Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory proposes, there are many environmental aspects which impact development, from peers, neighbours and family structures to social groups, policies and the media.

THE IMPACTOF LABELLING

The practice of labelling children is undermining their uniqueness and instead pigeon-holing children by a particular characteristic. Although some labels refer to a child’s academic potential, others are targeted at behaviour and personality, including ‘the quiet one’, ‘the one to watch’, ‘troublemaker’, ‘loud’ and ‘class clown’. Not only are these detrimental to a child’s wellbeing but they can also lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy. In this case, children begin to act accordingto their label, further influencinga child’s perception of themselves.

The practice of labelling children is undermining their uniqueness and instead pigeon-holing children by a particular characteristic. Although some labels refer to a child’s academic potential, others are targeted at behaviour and personality, including ‘the quiet one’, ‘the one to watch’, ‘troublemaker’, ‘loud’ and ‘class clown’. Not only are these detrimental to a child’s wellbeing but they can also lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy. In this case, children begin to act accordingto their label, further influencinga child’s perception of themselves.

Grouping children by ability can exacerbate this further as it can affect friendships and wellbeing. Children are not free to choose whom to engage with, instead their interactions are limited, at times, to the group of children they have been placed with (Webb-Williams, 2021).

Once a child has been labelled, it can be difficult to shift, following them from teacher to teacher. Usinga label can be an easy way to describe a child during transition meetings, but it will already be influencing the way a child is viewed.

This is problematic due to the implications related to the labels assigned to children. It can impact on their confidence, self-esteem and general wellbeing, influencing not only their education but their holistic development as an individual. Furthermore, labels can also be taken from school into the home as children talk about their peers. Unfortunately, this can impact on parental perceptions, leading to ‘don’t play with the naughty boy’ and other such statements.

EARLY YEARS WITHOUT LABELS

If we look to a future without labelling young children, we aspire to an ethos where holistic learning and development is valued. In practice, this means separating the child as an individual from the label attached to their academic ability or behaviour. The most creative child in your cohort might not be able to transfer their ideas through writing, but could be the most skilful thinker.

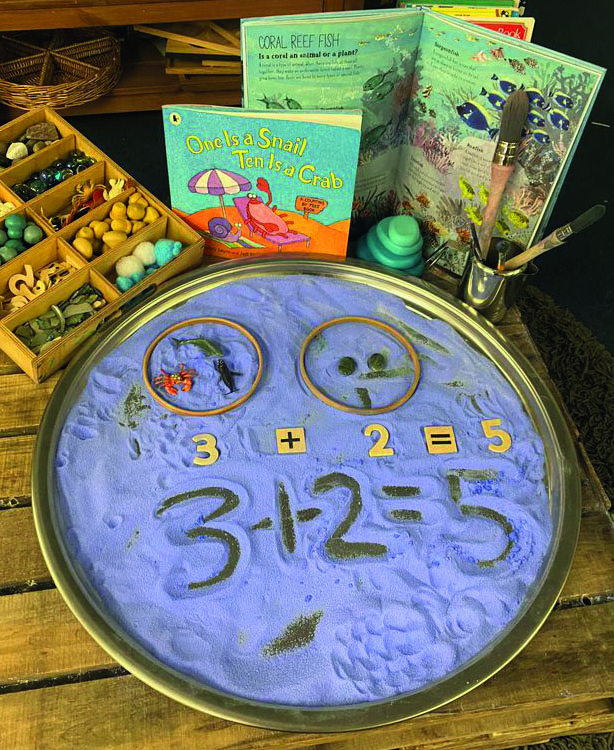

Let’s swap labels for connections, promoting an inclusive environment which nurtures kindness, care and love. This nurtures creativity rather than stifles it, enabling children to explore, be curious and test their own limits. Our environments in settings and schools can reflect this, with opportunities for children to challenge themselves, discover their talents and skills and enjoy the process of learning, rather than just be engaged for the purpose of an end product.

CASE STUDY: The Wroxham School

Lynn Cripps, deputy leader of EYFS, The Wroxham School

‘We don’t use any labels or groups by ability. We follow the approach of “learning without limits”, which takes away the notion of fixed ability and focuses on what a child’s potential can be. We look at our approaches in teaching and support each child with their learning, so ensure they achieve. If we label children or put a ceiling limit on what we expect they can learn, then we will never see their full potential. Their self-esteem and confidence over time will decrease and their enjoyment of learning will be impacted, leading to disengagement in school life.

‘We don’t use any labels or groups by ability. We follow the approach of “learning without limits”, which takes away the notion of fixed ability and focuses on what a child’s potential can be. We look at our approaches in teaching and support each child with their learning, so ensure they achieve. If we label children or put a ceiling limit on what we expect they can learn, then we will never see their full potential. Their self-esteem and confidence over time will decrease and their enjoyment of learning will be impacted, leading to disengagement in school life.

‘Once a child starts in Reception, the parents are quite often in a hurry for reading books with words as their child can already read. They like to know where their child is compared to others in the class with reading and maths. They’ll say “my Freddie can count beyond 20”, as if that’s all maths is.

‘Labelling of children should be avoided as it just inhibits development and can cause the child to be put off learning. Let them lead their learning and allow the grown-ups to support this. If Freddie wants to read books to others and not a grown up, let him – an adult can still assess while listening. If Freddie wants to use literacy skills to write a label or instructions for his model, that’s still writing/mark-making and can be valued in the moment by others. A child can feel very undervalued when their efforts are dismissed. If they feel they are in charge of their learning, then this can empower them to achieve their goals.

‘Giving a child the confidence to take a risk in their learning can be beneficial. Of course there are certain things that are required to be taught, but if the child feels valued in their learning and given space and time to extend their thinking, the impact will be seen in attainment. Children will just take learning in their stride and if they struggle, they know it’s ok and support is there for them. They then don’t see themselves as failures.’

REFERENCES

- Go to nurseryworld.co.uk to see the references for this article