Gender identity has been a hot topic in recent years. But to what extent does it apply to early years practice? Research evidence suggests that it is crucial.

Adults often subconsciously treat boys and girls differently, unintentionally reinforcing gender stereotypes. This happens through our interactions, the language we use and even the books that we share.

Seventy four per cent of parents agree that boys and girls are treated differently. Yet most educators have never received any training on challenging gender stereotypes (Fawcett, 2020). This matters because gender inequality can have long-lasting negative effects.

The gender pay gap, the lack of women in STEM professions, and the harm caused to men by ‘toxic masculinity’ – all of these things can be traced back to rigid ideas about gender, which we can work harder to undo during the early years.

For example, research shows that in early childhood there are no gender-related differences in children’s computational thinking ability (Kanaki et al., 2022), their motivation for coding or their ability to code (Master et al., 2023). Yet 85 per cent of students taking A-levels in computer science are boys. Why? Research suggests that around age six, boys believe they are better at coding than girls (Master et al., 2023) and children endorse the stereotype that computer science and engineering are less interesting to girls (Master et al., 2021).

This is compounded by a lack of role models and representation. A study of how technology is presented in children’s picturebooks found a heavy focus on males, with females only appearing in passive roles (Axell et al., 2019).

‘Gender stereotypes harm everyone,’ says Angharad Morgan, programme co-ordinator at Gender Action. ‘They place us all into binary boxes, impacting the way we develop, learn and view ourselves. Before a child is even born, their biological sex has determined how society will define them… from gender reveal parties to stereotyped clothes and toys, already society is making assumptions about a child’s characteristics.’

Gender Action is an award programme which supports settings to challenge stereotypes and put gender equity at the heart of policy and practice. The programme offers free training and one-to-one guidance for practitioners, as well as a framework to support and reward settings for creating lasting cultural change.

EQUALITY OR EQUITY?

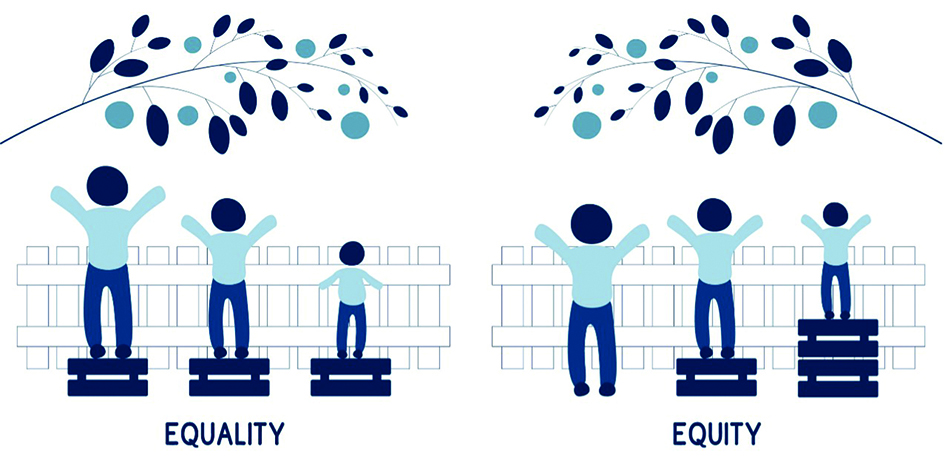

Gender equality means equal rights and outcomes for everyone, regardless of gender.

We can think of this as the end goal. Equity, on the other hand, is the means to get there. Whereas equality means everyone getting the same thing, this won’t work if we don’t all have the same starting points. In order to achieve equality, some individuals or groups might need extra support or resources. Equity means allocating the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.

STEREOTYPES AND MENTAL HEALTH

Gender stereotypes go beyond the toys children play with and the clothes they wear; they can also lead to children feeling pressured to display certain character traits or behaviours (such as kindness and obedience for girls and strength and bravery for boys).

This can limit children’s potential and create pressure to ‘fit in’ with norms, leading to poor mental health. When asked which traits are most important in boys, one in eight children said ‘being tough’. The boys giving this response had lower wellbeing than others in the group. Similarly, 44 per cent of girls felt that being ‘good-looking’ was girls’ most important feature. Girls who thought ‘having good clothes’ was most important had lower wellbeing than peers (Children’s Society, 2023).

IN SCHOOLS AND NURSERIES

A six-week experiment televised by the BBC (No More Boys and Girls) examined how a teacher interacted with boys and girls differently. It found that children were segregated by gender unnecessarily and that behaviour was rewarded differently.

After removing any gender-based inferences and introducing non-conforming role models, such as a female mechanic and a male ballet dancer, children’s assumptions about gender were challenged, leading to improvements in girls’ self-esteem and in boys’ behaviour and emotional expression.

Yet studies have shown that it is often children themselves who gravitate towards stereotypical gendered play and try to prevent others from challenging those stereotypes.

In a longitudinal nursery school observation (Martin, 2011), boys were seen to dominate construction and outdoor areas while girls dominated role play and writing areas. Children actively controlled access to these zones, challenging those who attempted to cross the gender divide.

Another study showed three-year-olds stereotypically relate toys, objects and colours to gender, and six- to seven-year-olds try to prevent counter-stereotypical behaviour (Skocajic et al., 2019). Forming stereotypes is a natural way in which children try to make sense of the world, but exclusionary practices prevent them from accessing certain forms of learning. Practitioners need to support children to engage with the full range of developmental activities on offer.

Definitions and stereotypes

What does gender equality really mean?

- Believing there are no inherent gender differences that should limit anyone’s interests, capabilities or ambitions (Gender Action).

- Taking into consideration the interests, needs and priorities of both women and men, boys and girls (Unicef).

Examples of gender stereotypes:

- Boys shouldn’t cry/‘man up’

- Girl are naturally calmer/more caring/more academic

- ‘Boys will be boys’

- Commenting on girl’s appearance but not boys, e.g. ‘I love your shoes/your hair looks so pretty today’

- Being more likely to ask girls to tidy up/carry out helpful tasks

- Being more likely to ask boys to carry/lift heavy things

- Assuming girls will not be as interested as boysin construction, technology, football and other stereotypically ‘male’ activities, and vice versa for boys with dolls, the role-play area, colouring, etc.

Statistics

- Worldwide, almost 25 per cent of girls aged 15 to 19 are not employed or in education or training. This is compared to only 10 per cent of boys (UNICEF, 2023). Women hold only 26.5 per cent of parliamentary seats worldwide (Global Citizen, 2023) and own less than 20 per cent of the world’s land (Concern, 2022).

- Only 4 per cent of CEOs at FTSE 250 companies are women (Statista.com), and the UK gender pay gap is 14.3 per cent (Statista.com).

- In the Western world, men die by suicide three to four times more often than women (WHO, 2015).

- In England, the suspension rate for male pupils is almost double that for female pupils (Gov.uk, 2023).

- In England, only 2 per cent of early years educators are male. This has barely changed in a quarter of a century (EYE, 2023).

- There is a persistent gender imbalance in A-level subjects. In 2022, 94 per cent of students studying performing or expressive arts, and 77 per cent of students studying English literature, were female, while 75 per cent of physics students were male (Twinkl.co.uk).

CASE STUDY: tackling gender inequality

A report published by UN Women in 2022 suggests it could take almost 300 years to reach full gender equality at the current rate of progress. To change this, it’s not enough to be ‘gender neutral’; gender stereotyped views need to be actively challenged. If settings are unsure of how to go about this, Gender Action can help.

After hearing children make comments like ‘Boys can’t do ballet’ and ‘Girls can’t play football’, as well as noticing a significant gender attainment gap in the EYFS, with girls outperforming boys, Pitmaston Primary School joined the Gender Action programme.

Vicky Snape, early years phase leader at Pitmaston, says, ‘We’ve changed our curriculum to include Mae C. Jemison when we are learning about space and read the book Astro Girl. We have also introduced books that promote gender equity such as Sparkle Boyand Julian is a Mermaidto ensure all pupils are exposed to books that constantly challenge gender stereotypes.’

Angharad Morgan at Gender Action says, ‘It’s great to see how staff and parents can work together and educate each other. Children can feel freer to express themselves, interact and have role models from parents and staff that give them the opportunity to be who they want to be without the restrictions of gender stereotypes.’

- You can find out more about the free programme and how to sign up at https://www.genderaction.co.uk/getting-started

REFERENCES

- Please refer to the online version of this article at nurseryworld.co.uk for a full list of references