Download this article as a pdf

The 70s was a time of great change: we had the Sex Discrimination Act and the Equal Pay Act, which were both concerned about the lack of childcare.

Only a third of children aged two to four attended any kind of state-provided or registered childcare in 1978, a newsletter from the National Association of Teachers in Further and Higher Education reported. There were signs that this was despite a desire of more women to work, not because of a lack of it: the same year the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) reported a 1974 survey showing that 64 per cent of mothers wanted some form of daycare for their under-fives.

Yet when I was pregnant in 1972, and knew that I wanted to continue my lecturing career, there were no day nurseries that I could access. Local authority day nurseries and family centres were available for children deemed at risk in some way, but not for the use of those with two employed parents.

- See Helen Penn on the rise and fall of childcare ambitions

- Childcare policy: 20 years on

- Childcare shortage excludes 870k women from workplace

- What can government's do to encourage women to have babies?

My options were to find a childminder through the inadequate and out-of-date lists held by the local authority, find a neighbour willing to look after my child, or get an au pair.

One of the problems was that there were so few places available. Local authorities were not under any obligation to assess demand in their area until it became law in the Children Act of 2006. The total estimated number of under-fives in any form of care in 1973, including those placed with childminders, was one million. Almost all of this care was part-time.

This was the situation which led to women in all parts of the country beginning to get together to try to find their own solutions. We were arguing for publicly funded free provision, workplace nurseries and nurseries in colleges.

We finally established the National Childcare Campaign in 1980, which led to the creation of what is now Coram Family and Childcare (recently known as the Family and Childcare Trust).

Have things improved?

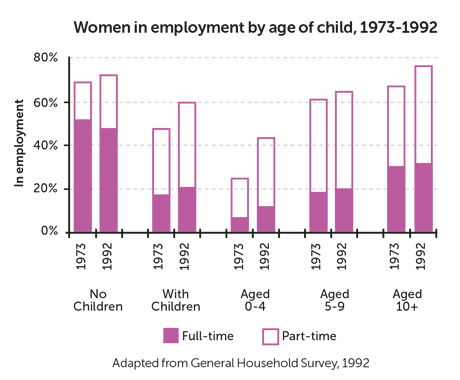

In 1973, just 7 per cent of women with children under five worked full-time, and this figure had not changed much by 1992 when it was 11 per cent (see chart, below).

Conversely, 18 per cent of women in this category worked part-time, but by 1992, this had almost doubled to 31 per cent.

I have had to do my own analysis of labourforce statistics to look at the more recent picture, from 1996 to 2018.

My analysis (see table, below) shows there has been a 12 percentage point increase in women with children under five employed full-time since 1996 and a 3 percentage point part-time increase.

If we go back to the 1970s, there is an increase in women in work, from 53 per cent in 1971 to 71.2 per cent in 2018 (Office for National Statistics (ONS)). Also, there has been an increase in the number of women with children in work, from 44 per cent in 1973 to around 74 per cent in April-June 2018 (ONS).

But a large part of the increase in mothers’ employment has been in part-time work, which tends to be worse-paid. When the table (below) is broken down into age by child, we see that most women are not employed continuously. By the time their child is one year old, more women will be working part-time than full-time.

In fact, mothers with children aged between one and 11 are more likely to be in part-time than full-time work, and don’t catch up with their pre-childbirth work rates for over a decade. It is not until the youngest child is 13 that the full-time work rate (43 per cent) exceeds that for when the youngest child was under one (41 per cent) – women are counted as full-time employed if they are on maternity leave.

Are there enough places?

If a full-time employed woman wants to continue in full-time work, after maternity leave, when her child is under three years old, is it possible to find affordable, good-quality childcare and early education?

Again, such data is not readily available so I have made some calculations to get a handle on the number of full-time places available. The calculations look at specific age groups, so it is worth noting that support for those eligible is available for all parents of birth to fives in the form of schemes such as Tax-Free Childcare (though 80 per cent of eligible parents haven’t signed up) and benefits. Here is a summary:

1. There is no funded provision for children aged birth to one.

2. On two-year-olds:

a) Funded provision is available for some (15 hours for the 40 per cent most disadvantaged). But how many places are there versus the number of two-year-olds in total? The Government’s claim that 72 per cent of eligible two-year-olds took up a funded place tells us little about the number of funded places per population of all two-year-olds. In 2018, 154,960 eligible two-year-olds received funded educational provision out of a total population of 696,271 (the birth rate in 2016).

b) This means 22.5 per cent of all twos have a funded place.

3. On one-year-olds:

a) There were 679,106 live births of children born in 2017. The DfE’s Survey of Childcare and Early Years Providers estimates the total number of full-time places in group-based (not school) provision for all children under five in 2018, was 1.1 million places. If we hypothesise that most of these group places are for birth to four-year-olds, i.e. for five separate cohorts, then we can estimate there are 220,000 places per age group (1.1 million divided by 5). We can see there is a large shortfall between the hundred thousand estimated number of nursery places per age group, and the 679,106 one-year olds who might want places. It leaves us potentially 459,106 places short.

b) From three years old there are more childcare places in other types of settings such as schools, so let’s try making the assumption that the group-based places are all used for birth to two-year-olds (i.e. a three-year cohort of children aged from birth to one to two). If we divide the total number of these full-time places by three, we get 366,667 places available for one-year-olds, but this still leaves the potential shortfall of 312,439 places for a population of 679,106.

c) If we add in the 243,000 childminder places in 2018 (although these are not necessarily full-time): 243,000 divided by three (for birth to twos) equals 81,000 places. Added to the figure of places in full daycare settings for birth to twos, we get 447,667. This still leaves us short by 231,439 places. So even when childminder places are added, the shortfall for one-year-olds is well more than 200,000 places.

1996 2018Full-time 17% 29%

Part-time 33% 36%]]