Play is central to children's lives. It is the way they make sense of the world around them and the circumstances they find themselves living through. So, it is not surprising that researchers want to capture and preserve a record of children's play during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The scale and nature of how the pandemic has impacted children's play as yet remains unknown, but it is indisputable that life changed dramatically in early 2020. With nurseries, schools and playgrounds closed, children were restricted to where they could play, and with whom. Many of them played alone or with siblings and family members, indoors or in their gardens, if they were lucky enough to have one.

CAPTURING PLAY EXPERIENCES

Anecdotal evidence suggests that aspects of the pandemic have filtered through into children's everyday play. Mask-wearing, hand-sanitising and social distancing are part of the new world we live in, and children as young as two years old associate wearing masks with their parents going to the shops.

Professor Helen Dodd of the University of Reading, who is leading a project in collaboration with the Museum of English Rural Life to form a Pandemic Play Archive, says, ‘Various themes are emerging in children's play. We’re seeing lots of games involving battling, splatting and dodging, which suggest children are trying to control the virus. They are also trying to recreate normal life and they are bringing new ideas and concepts into their play, which did not exist before.

‘For younger children, much of their pandemic play involves masks and hand sanitiser: things they can see. And for older children, more complex themes such as vaccinations and medical procedures are taking place.’

Professor Dodd reports that the other theme that stands out is social interaction. ‘Children are demonstrating a need to feel connected, whether this is through technology, having a teddy bear, pet – or even a cardboard cut-out – replace a best friend. I’ve seen examples of children socially distancing their Barbie dolls or teddies during their play. One practitioner spoke of a child who set up a small-world play tea party but had to turn two “friends” away because only six were allowed to be together.’

New study

Just as Ring a Ring o' Roses came about as a result of the Great Plague, Covid-19 has given birth to Covid Tiggy, which involves touching elbows, or Shadow Tag, which avoids touching altogether.

Researchers at UCL Institute of Education, the University of Sheffield and UCL Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis have been documenting the many ways that children are playing since the outset of the pandemic: by themselves and with others, indoors and outdoors, with and without screens.

Their previous work includes Playing the Archive, a project involving a collection of play practices throughout the ages inspired by Peter and Iona Opie, who undertook a national survey of school children about their play in the 1950s.

In March 2021, the academics received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council to launch the Play Observatory, which captures children's play experiences though an online questionnaire for children in the UK and abroad.

Dr Kate Cowan, early years specialist at the Centre for Multimodal Research, UCL Knowledge Lab, who is working on the project, says, ‘We’re interested in new play that has emerged and how play has continued, changed or adapted. Data collection is ongoing, but so far the examples show new versions of traditional games, like Covid Tiggy and hybrid forms of onscreen-offscreen play. For instance, a family in Germany told us about their four-year-old building a toy house and playing with it virtually with his grandmother.

‘One ten-year-old from Leeds didn’t want people to come near his house and act like Covid didn’t exist, so he did chalk drawings on his drive of a ghost, a bowl of poison, a skull and crossbones, and he wrote “Keep Out”. His sister drew a creeper from Minecraft. He named this activity Pandemic Panic Drawing.’

Digital play

Dr Cowan reports that digital play has also been an important part of children's play during the pandemic. She says, ‘An eight-year-old from Taunton told us, “I have been doing Roblox with a friend in Singapore … It made me feel happy because I connected with a friend through a game.” Brothers aged eight and 13 from Sheffield shared an example of a coronavirus clinic they had built in Minecraft, complete with an outbreak lever and antidote.’

She adds, ‘These early examples seem to be giving us an insight into play's resilience and adaptability even when it faces restrictions and shines a light on how important play is for children perhaps now more than ever.’

NOT ALL PLAY IS COVID-RELATED

Despite the early themes that are emerging, academics agree that not all play is Covid-related. There are many examples of children riding bikes, flying kites, making sandcastles and building models.

PhD student Kelsey Graber, who is leading a study for the University of Cambridge's Play in Education, Development & Learning (PEDAL) Centre, interviewed 15 children to discover their experiences of play during lockdown.

She says, ‘The study, Play in the Pandemic, puts play and children's voices at the forefront. I was expecting to see more play related to the pandemic, based on reports from parents. However, children told me that their play was still normal and typical and happening – and that's also part of the story of what it's like to play in the pandemic, even though it's not overtly related.’

Professor Dodd also noted that there are many parents, early years practitioners and teachers who say that they ‘have not observed anything’ and that children are ignoring the virus. They don't talk about it, they don't play in this way and they just want to get on with their lives.

She adds, ‘I think it's important to note that not all of children's play has been hijacked by the virus, but I think that if we look for it, there are subtle themes of the virus, even in the play that might look regular.’

RESILIENCE OF PLAY

What stood out to Ms Graber when she interviewed 15 children aged three to ten years during August and September 2020 was the resilience of children's play during the pandemic.

Much of her previous research focused on the intersection of play and children's health, particularly in paediatric hospitals. Therefore she was expecting there to be correlations with the way children played during lockdown.

However, what she found was that despite being in the midst of a global pandemic, children's play persisted.

She says, ‘It was clear that play itself was certainly not on lockdown. When children are in hospital, especially six- or seven-year-olds who are starting to become more social, one of the main challenges for them is missing out on things that their peers are doing.

‘But during lockdown it was wonderful to see the resilience and persistence of play emerging no matter what.

‘The children described ways in which their play felt normal and typical: playing in the garden, making up new games with siblings, writing stories and drawing pictures. That's not to say that their play has been unaffected. Children described ways that play felt different, such as not being able to hug or touch non-immediate family members, virtual birthday parties and games that had changed at school because of social distancing.’

During the interviews, children were asked to bring with them their favourite toy or game as an ice breaker. One child, aged three, showed off an area of her bedroom that had been turned into an imaginary doctor's office, with various stuffed animals needing to rest because of ‘germs’.

Ms Graber says, ‘The child told me I could keep my own stuffed animals safe by covering their noses and mouths, which she demonstrated using a piece of cloth as a “mask”.’

Although Ms Graber accepts her study's, limitations she says it is important to note she was grabbing ‘a moment in time’ that is a small picture of what was important to that child at that time – she says it is still valuable to pay attention to these 15 children.

FUTURE GENERATIONS

For future generations looking back at the play archives being developed, Professor Dodd says, ‘In 100 years’ time, it would be interesting to see if children still play games like Covid Tag as a legacy to the pandemic. Or whether playground games might include some kind of virus. It's most likely to be maintained through playground play because there, hundreds of children get together and games spread easily.’

MORE INFORMATION

- Professor Dodd and researchers at the University of Reading have created an online Pandemic Play Archive where a collection of memories depicting examples of children's play has been showcased at the Museum of English Rural Life. Contributions are ongoing and they would welcome examples from practitioners working directly with children, at: https://pandemicplay.live/MERL

- The Play Observatory's (https://www.play-observatory.com) collection will be shared in several ways: there will be a searchable online collection of examples, with selected material deposited with the British Library to preserve a record of children's play for future generations, and an online exhibition at the V&A Museum of Childhood will be launched later this year. Contributions are also ongoing.

- The Opie Archive, https://www.opiearchive.org

- Playing the Archive, https://playingthearchive.net

Snapshot of pandemic play: case studies from the Pandemic Play Archive

In her capacity as a child psychologist, Professor Helen Dodd provides a snapshot of some of the submissions to her play archive. She highlights what parents have had to say in their own words about their children's play and provides comments on why they might be playing in this way.

Physical responses to the virus

- ‘My son (aged two) held a small board book up to my face and said, “mummy has got mask on now, can go to shop.”’

Professor Dodd: ‘This is quite striking because the child is so young. He probably doesn’t understand why the mask is there and what it's for, but he's old enough to realise that when we go to the shop, mummy puts a mask on. So it's a very physical thing.

‘Other examples of the physical world coming into play we’ve observed are children creating hand sanitiser or making people put hand sanitiser on when they come into their shop during role play. It doesn’t rely on them having a really good understanding of the virus or what hand sanitiser does, but it's a new routine in our lives that children have observed adults doing – and they are adapting or recreating their play as a result.’

Recreating normal life

- ‘In early lockdown, my two- and four-year-old's usual Sunday routine – swimming lessons followed by a drive-through Costa – was cancelled. For the first few weeks, the children “swam” in the living room using the furniture to replicate what they did in the pool. Then they set up a car, loaded their toys in and pretended to go to Costa. I supplied babycinos and chocolate tiffin.’

Professor Dodd: ‘These children are adapting to a change in circumstances in a playful way. It's almost like they knew intuitively what they needed: it needed to feel like Sunday and this is what they did on Sunday, so they decided to do it in their play.’

Role play

- ‘My daughter's favourite game has been pretending to be sick and having another child or adult be the doctor/veterinarian helping her.’

Professor Dodd: ‘Parents have reported that play relating to illness has been more regular and focused during lockdown. Mostly, it is general themes around hospitals and medication, rather than being specifically about Covid. But, occasionally, someone has the virus. They are more aware of the NHS, keeping people safe and physical health, and this is likely to be stimulating this kind of play.’

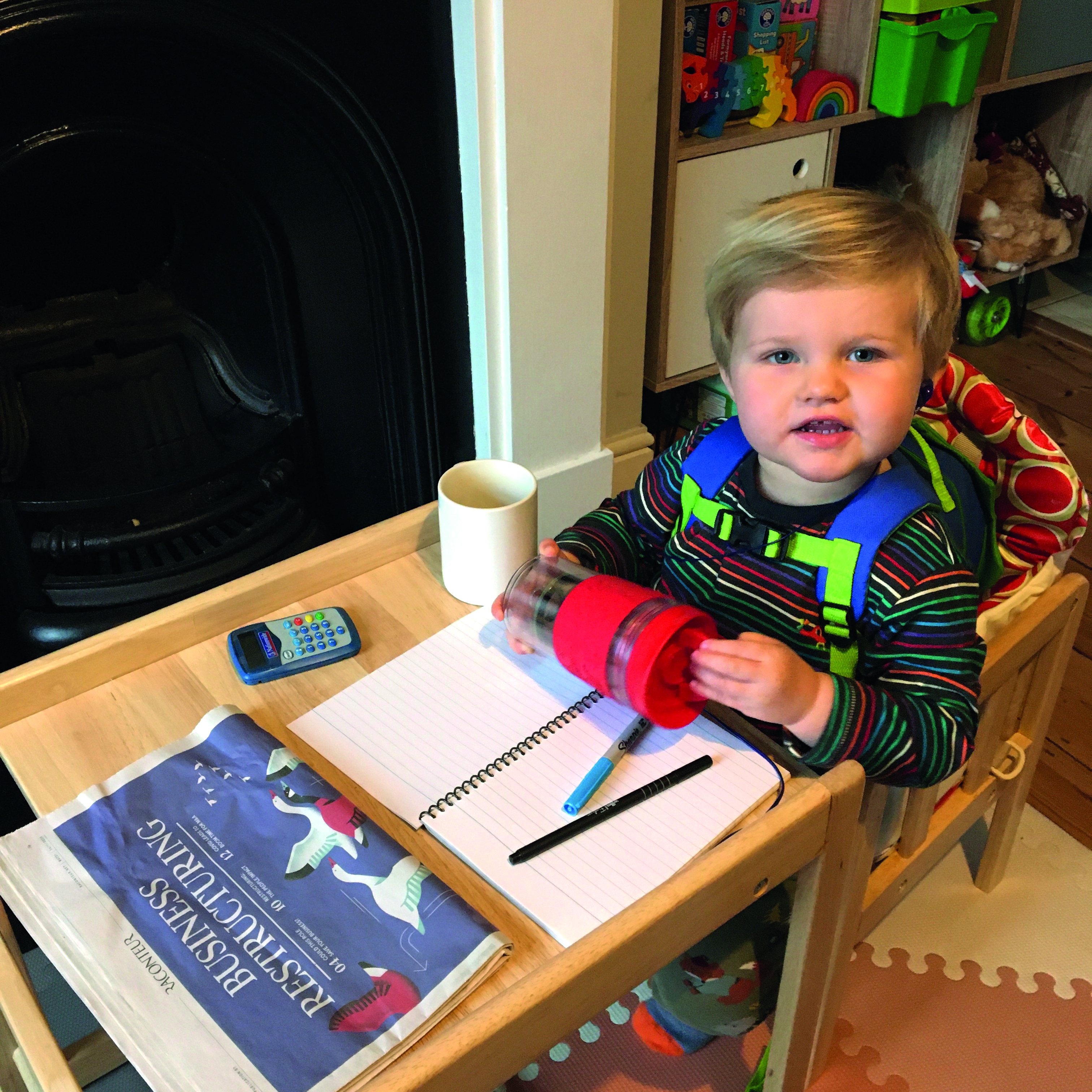

- ‘My two-year-old son likes “working from home”. My husband has been working from home since the start of the pandemic, and my son often role-plays “going to work” at his “desk” in the living room. He puts his backpack on and makes sure he has a plentiful supply of “coffee”!’

Professor Dodd: ‘This example shows a child role playing something that he's observed which is new to the adult world – and unique to the pandemic.’

Covid-specific

- ‘My three-year-old son often plays with trains and cars. He gives them voices and uses them like dolls. He once had this conversation:

“Car 1: I wish Tristan could come play with us.

“Car 2: Me too. But we have to wait until we have a shot. The sickness is bad. And Tristan isn’t being as careful as we are.

“Car 1: I know. I wish Covid would just go away. People need to wear their masks. Whenever they don't, the sickness gets longer and longer.

“Car 2: Yeah. Let's play on the track!”’

Professor Dodd: ‘This is specific about Covid, vaccinations and the need to wear masks. It's a slightly older child so there's a bit more of that understanding of Covid, as opposed to the two-year-old putting a mask on but not understanding what it's for.’

Control over the virus

- ‘My daughters (aged four and six) spent time creating a medicine for the virus from things found in the garden. They put on dressing-up clothes – a cape and mask – to protect them from “all the chemicals” and spent time mixing the medicine. Then they tested it out on their toys to see if it would work, adjusted it a bit more, and gave it to the family.’

Professor Dodd: ‘It's unusual to see this form of crossover play between medicine and superheroes. The play here is more complex and the children, who are older, have a deeper understanding of how medicine can be used.’

Adapting to change

- ‘Our nine-year-old daughter created a cardboard cut-out of her best friend and took her around with her everywhere in the house. She played games with her and talked to her as if she were real. The height of this was during the weeks where we were anxious about her grandmother making a flight to be with us and it really helped her get through the time. As soon as her grandmother arrived, she stopped playing with the cut-out friend almost overnight and never went back to her.’

Professor Dodd: ‘This feels like a response to anxiety. It's a much older child and developmentally, it's interesting to see the difference. Not only does it demonstrate an understanding of Covid but it also reflects anxiety. Recreating the presence of someone that she finds reassuring is an adaptive thing to do if it works for her and makes her feel safe and connected, it's a good thing. However, if she started to go to school with the cardboard cut-out it might get concerning. It's unusual, but we’re living in unusual circumstances.’