The early years setting, whether a nursery, a childminder or a school, is one of the first spaces in which children become aware of their social identity, including their learning abilities. Within those first few years, young children are navigating many new experiences in which they are gradually figuring out whether they are welcomed and belong or simply trying to find a way to fit in.

Sadly, any space that narrowly pre-determines who children should be and what they should learn is also a space in which ableism can flourish. Simply put, ableism is the societal belief that disabled bodies and minds are an unwanted difference. Ableist systems, therefore, focus on preventing, fixing, curing or treating disability rather than advancing inclusion and accessibility for all. As a sector, we are primed to believe that early child development falls within the binary categories of ‘normal’ and ‘special’. And through the early identification of a child’s unwanted difference, we are assured that early intervention can reduce a child’s deficits. All of this is wrapped up within the EYFS principle that children are unique and ‘constantly learning…capable, confident and self-assured’ and that they ‘develop and learn at different rates’ (DfE 2021).

And yet, by the toddler years, we are already required to assess whether that unique child is typically developing, showing ‘red flags’, giving us concerns or presenting signs of a delay. It is important to stipulate here that we absolutely have a duty to ensure that every child can thrive, and our ability to recognise when development is not following the usual path is crucial in providing the right support.

But I often question why we are only ever trained to ask ‘what is wrong?’ rather than ‘what is different?’ regarding child development. This distinction in language is important because, increasingly, we see more children with ‘emergent neurodivergence’ (Conkyabir 2022), such as autism, ADHD and dyslexia, to name a few. These are lifelong neurotypes, so if all our questions focus on how to fix the apparent wrongness of these children, how might they form a positive identity across their lifespan? Furthermore, if our so-called systems of support sustain the idea that to be different is wrong, we must challenge whether they lead us to further stigmatise and discriminate against children who go on to receive a developmental diagnosis.

There is no greater time to pose these challenges, as our country’s review of SEND provision found that services are failing children and families, and we continue to see poorer outcomes for children identified with SEND (HMI 2022).

ABLEISM IS THE SYSTEM… DISABLISM IS THE ACTION

For many years, I have worked as a special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) specialist and advised early years practitioners on the best ways to address developmental delays, which I now understand was built upon ableist ideas. For example, I set goals that required autistic children to play more appropriately or to provide eye contact during interactions.

It was quite confronting when I learned that most of what I had been trained in promoted ableism. I realised I had been utilising early intervention like a blanket ‘find it and fix it’ tool. And so I began to explore the different practices and their prevalence in early childhood. I discovered the work of scholar Dan Goodley (2016), who explains that ableism relates to the wider belief system that able bodies and typical minds are favourable, and disablism is where we consciously and unconsciously put this belief system into action through our everyday behaviours, practices and thoughts.

Disablism also includes the negative internalised ideas that disabled and neurodivergent children develop about themselves based on their experiences of exclusion. When these children realise that they are viewed through a deficit lens, they begin to mask (hide) those parts of themselves that are not considered acceptable. Some examples of ableism and disablism are outlined in the table (opposite).

When educators begin to explore ableism, I am often asked how we can challenge such practices when they are so deep-rooted and often seemingly beyond our control. There is no straightforward answer to this, particularly as the pressures on children seem to intensify with every passing year. However, like many things, it is hard to unsee once we begin to see something. And with this emerges the opportunity for reflection and action. In my own reflections, I have started to identify several areas of focus where we can begin to dismantle and disrupt ableism. Here we will focus on play and communication.

PLAY NOT PATHOLOGY

‘Play must be the right of every child. Not a privilege. After all, when regarded as a privilege, it is granted to some and denied to others, creating further inequities. Play as a right is what is fair and just. Although children will engage in play differently, play is a child’s right.’

Souto-Manning (2017)

One of the areas in which we see ableism occur is through the pathology of children’s play. There are countless times I have uttered the words ‘play does not come naturally to children with SEND’, or I have viewed every behaviour as a symptom rather than a play trait. For example, many of us will resonate with the autistic trope of ‘all he does is line things up’, or ‘she doesn’t engage in imaginative play’.

These views have come to be because of the ableist belief that neurodivergent or disabled children must be taught how to play and behave in neurotypical ways. Neurotypical play is often achieved through adult-led play-based intervention. This can take children away from what they need most… uninterrupted child-led play in spaces where they feel safe and secure, facilitated by trusted play protagonists. Intervention, if required, should meet the child where they are developmentally, and it should be firmly rooted in the child’s interests, wellbeing and enjoyment. Play-based interventions may tick a box on an individual education plan (IEP) or prove that they have engaged in early intervention, but how truly valuable is that for the child, and what meaning does it hold for their divergent development?

The case study (opposite) is one of many I have collated in recent months, challenging the idea that disabled and neurodivergent children need to be removed from their play. Early years childminder David Cahn, who also authored the book Umar about a child’s special interest in keys, recently explained to me, ‘We spend our time thinking we need to do all this stuff to make children better, without realising that they are already fantastic and doing many fantastic things.’

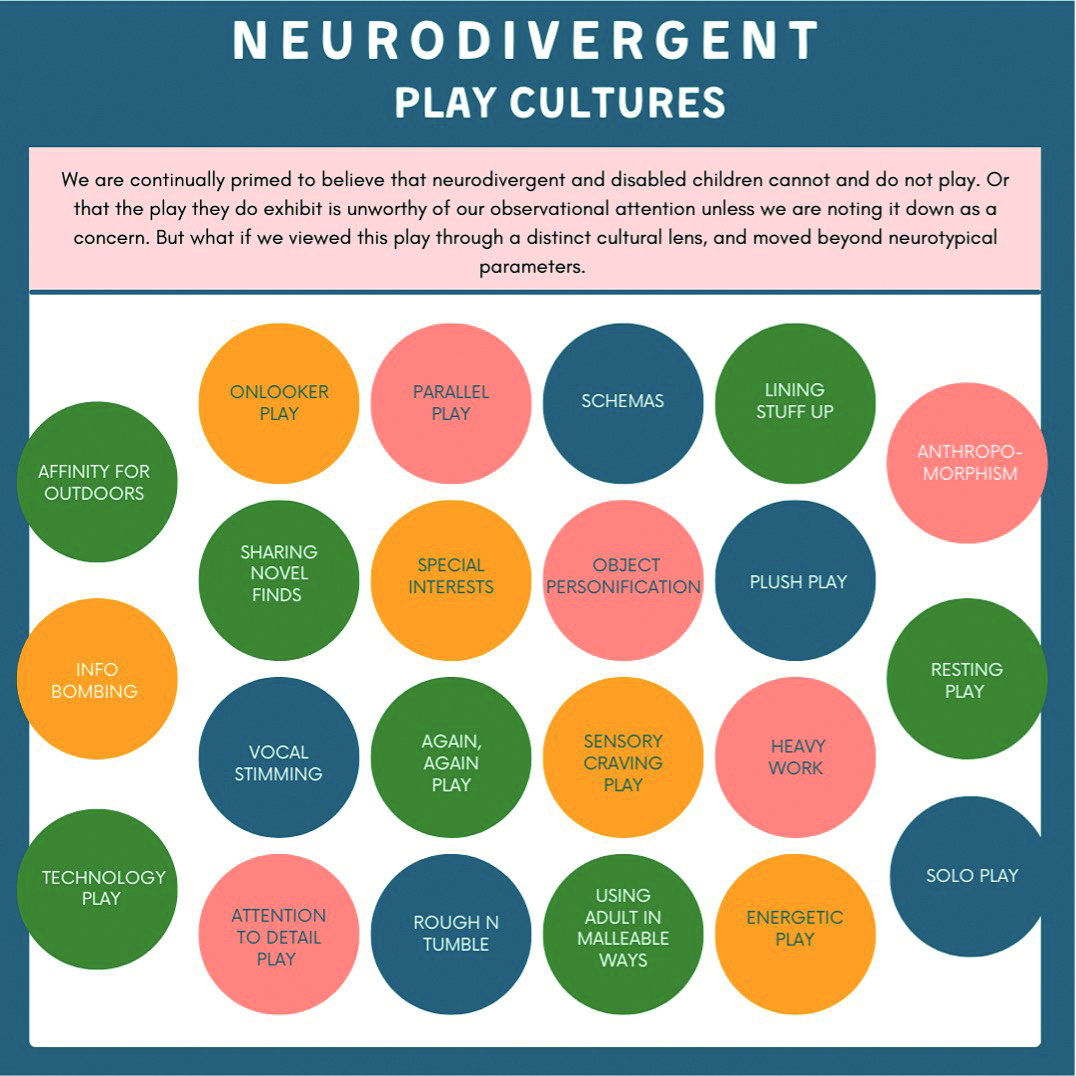

Some examples are highlighted in the graphic.

ABLEISM IN COMMUNICATION

Another common area of need in the early years is speech, language and communication (SLCN). Many of us are familiar with the statistics around SLCN and the importance of overall communication being a crucial life skill. This area of need, however, has also been used to create further stigma and discrimination toward certain groups of children. For example, our current frameworks for understanding and assessing children’s development favours spoken language even though some of our children will be non-speaking, minimally verbal and may prefer alternative forms of communication. While spoken language is important and should be encouraged, we must also acknowledge that communication is diverse, and a range of needs must be accommodated.

COMMUNICATION IDENTITY

Brodin and Renblad (2019) refer to a powerful idea that when children come into our early years settings, a communication identity is already forming. As practitioners, we must consider how we show respect and value towards this unique formation of culture, communicative experiences, early interactions, language, and family habits. While we may identify differences and delays in aspects of their communication, our approach mustn’t diminish their broader communication identity. During training, I often ask practitioners to think about their own communication identity. For example, we explore their accents, languages, body language, facial expressions and preferred ways of communication, such as through text, socially or one-on-one. This helps practitioners to understand that we should give observational value to the richness of our communication identities and not base our assessments entirely on the quantity of language rather than the overall quality of communicative experiences.

SOCIAL SKILLS AND WHOLE BODY LISTENING

Whole-body listening is commonplace in early childhood settings and, more often, in schools. The problem with this practice is that listening, attention and engagement can vary from child to child and, like many aspects of development, it is diverse. The premise is that children all need to abide by the same neurotypical social rules. Social awareness is important for early learning as we can become ableist and disablist when we set up practices that only promote neurotypicalism and conformity. You can find a more detailed post on this via my Instagram (@eyfs4me).

|

Whole Body Listening |

Neuroinclusive Listening |

|

Eyes on me Golden rules often include an insistence on providing eye contact to the adult or facing forwards. This is deemed necessary for attention. |

Look where feels comfortable Developmentally and culturally, eye contact can vary. For an autistic child, eye contact can feel overwhelming. Dropping eye contact can support the child to pay attention to what is being said and can help with sensory regulation. We should never demand eye contact as a goal. |

|

Sitting Still Children are often told to sit and stay still. This can s include stating the position that they sit in, for example, demanding that all children sit with their legs crossed. |

Sit in a way that feels comfortable and feel free to change position Children, and adults often need to move to be able to think and engage. Our bodies are not designed to be still. Movement can be a sign of engagement or disengagement. We need to be responsive to both. For example, a child may move because they are excited by the learning. Telling them to sit still communicates a confusing message that their engagement is not actually important. Alternatively, children move because they are restless or struggling to stay focused. In these scenario’s, we need to provide an active or calming movement break to ensure they can remain well regulated. Furthermore, disabled and neurodivergent children may engage in self-stimulatory behaviours (stimming), and this should never be stopped unless through consensual co-regulation or safety.

|

|

Silence and mouths closed Activities such as circle times provide great opportunities for oracy and communication. Yet, children are often “shushed” or told to stay silent indicating to the child that the adults voice is more important. |

I know you are excited to join in. If you can, try to reach your hands to the sky so we can make sure everyone is heard. A communicating child is an engaged child, and by demanding silence we are doing the opposite of what is needed. Yes, children absolutely need to be socially aware and sensitive to different ways of communicating, but silence is not the way to practice this. Use a variety of methods to empower the child’s “voice” and plan for impulsive engagement, such as “ready, steady…go”. |

WHAT CAN WE DO TO BECOME NEURODIVERSITY-AFFIRMING?

- Explore our language, and how we describe children, for example in affirming ways that embrace strengths or differences or via deficit terms such as ‘special’, ‘impaired’ or ‘delayed’.

- Be mindful that neurodivergent and disabled children are not represented in our main frameworks and curriculum. While we may see additional tools and resources which are fantastic, such as the Penn Green Celebratory Approach, we must continue to challenge child development documents that present typical development as ‘the norm’.

- Access neurodivergent and disability-led/collaborative training and guidance. An increasing number of organisations and trainers deliver through a lived experience and deeper understanding of ableism and disablism.

- Engage in critical reflections and discussions with other early years practitioners to unpick potential ableist and disablist practice. Consider new ways of developing your practice to be inclusive of all children.

Key terms

SEND is well known for its tricky language and jargon, making it difficult to access. It is important to emphasise that while language matters, there is no rush to suddenly integrate this new terminology into your pedagogy; rather, it is a way to ignite your curiosity in developing a new approach to inclusion that truly centres all children as competent, capable and unique.

Neurodiversity This relates to the biological fact that human brains and minds differ from each other. Neurodiversity aligns with the idea that all children are unique and ‘develop and learn at different rates’ (DfE 2021).

Neurotypical Having a mind that functions in a way that aligns with the social construction of ‘normal’ or typical. For example, children who meet typical milestones. Educational frameworks are predominately designed for neurotypical children.

Neurodivergent Having a mind that functions in ways that diverge from what society typically defines as ‘normal’ or typical. For example, being autistic or dyslexic. When children’s development deviates from what is considered normal, they are often viewed through a deficit lens of problems, impairments and delays.

Neurodiversity paradigm A paradigm basically means a perspective or set of ideas. The neurodiversity paradigm rejects the deficit lens and perceives brain differences as natural and valuable, meaning there is no ‘normal’ or right brain. It advocates that all minds have unique potential.

Ableism This is discrimination in favour of non-disabled people. It is the belief that it is better to not have a disability than to have one. Ableism is a system of assigning value to people based on the socially constructed idea of being ‘normal’ or ‘typical’. For example, believing that all children must present a good level of development in the same way and at the same time through neurotypical milestones, goals and outcomes.

Definitions adapted from Dr Nick Walker (2014) and Talila A. Lewis (2022). A full list of useful definitions can be found at Nursery World and here.

CASE STUDY: ‘special interest play’

Roz explained that she was caring for an autistic child who had a special interest in diggers, and he was currently using echolalia and non-verbal communication.

Roz explained that she was caring for an autistic child who had a special interest in diggers, and he was currently using echolalia and non-verbal communication.

When the Area SENCo visited, she expressed concern that the child’s play was repetitive and restricted and that a greater focus should be placed on developing functional play skills.

The area SENCo advised that Roz should deter the child from playing with diggers and introduce new toys that might ignite more language. Roz explained that more attempts at communication, including verbal and non-verbal, were being used when the child was able to engage in his special interest, and that diggers helped maintain his emotional regulation skills.

The area SENCo explained that he couldn’t just play with diggers forever and continued to set a target based on diverting his ‘obsessive’ attention from his special interest.

When I spoke to Roz about this situation, she decided to forgo the advice, stating that she had personal knowledge of the child and so felt she had to prioritise his right to special interest play. Ignoring specialist advice felt risky and uncomfortable, but Roz was transparent with the area SENCo and clearly outlined a personalised plan. This, she explained, paid off.

‘I doubled down in my observations of the child and realised it wasn’t just about the digger as a vehicle. The child was interested in the physical process of digging, unearthing and transporting,’ she said.

Roz also discovered that the child’s parents spent lots of time outdoors due to a refurbishment, and the child would often be a ‘helper’ and get involved in helping daddy with the jobs. This special interest had emotional connections.

Over time, Roz noticed that when she incorporated strategies around his special interest play, the child was much more engaged, his communication skills developed, and his interests did expand.

REFERENCES

- Conkbayir M (2021). Early Childhood and Neuroscience: Theory, research and implications for practice. Bloomsbury Publishing

- Goodley D and Runswick‐Cole K (2010). ‘Emancipating play: Dis/abled children, development and deconstruction’, Disability & Society, 25(4), pp.499-512

- Goodley D (2016). Disability Studies: An interdisciplinary introduction. Sage

- Souto-Manning M (2017). ‘Is play a privilege or a right? And what’s our responsibility? On the role of play for equity in early childhood education’, Early Child Development and Care, 187(5-6), pp.785-787

- Working definition of ableism

- Development Matters

- Summary of the SEND Review

- ‘Whole Body Listening… is it really that bad?’

- Brodin J and Renblad K (2020). ‘Improvement of preschool children’s speech and language skills’, Early child development and care, 190(14), pp.2205-2213

Kerry Murphy is an early years lecturer and consultant, specialising in wellbeing, behaviour and special educational needs. She is a lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London and author of A Guide to SEND in the Early Years.

Kerry will be speaking at Nursery World’s conference ‘EYFS: Supporting every child to thrive’, in London on 9 November. Find out more here