I am writing this article at a time of unprecedented upheaval, with much stress and uncertainty. We are all dealing with events, knowledge and situations not previously experienced, and their long-term impact on children and families is, as yet, unknown.

Once a crisis of this magnitude is over, it is tempting to think about ‘getting back to normal’. However, crises can be a starting point for thinking and doing things differently, and for positive changes. So, it seems timely to be thinking critically about the early childhood curriculum, and the professional knowledge, values and beliefs we draw on to guide our work with children and families.

I will start by looking at how curriculum is understood in the Early Years Foundation Stage, in light of the pervasive influence of Ofsted. I will highlight the limitations of how the Early Learning Goals (ELGs) are framed, and the focus on children’s individual developmental pathways. Looking beyond the ELGs, I will then propose some questions about what knowledge matters, whose knowledge matters, and why.

I realise these questions have many possible answers, so these two articles are springboards for curriculum conversations – thinking, talking and reflecting in your own settings, and in relation to diversities in your families and communities. Although the focus here is on the EYFS, these questions are relevant for practitioners across the UK where different policy frameworks are in place.

THE EYFS: SKILLS, KNOWLEDGE AND BEHAVIOURS

Curriculum in early childhood education (ECE) has been framed in many ways, as approaches (for example, Montessori, Steiner, Reggio Emilia) and as play-based. Curriculum arises from children’s choices, activities and experiences, building on the knowledge they bring from their homes and communities. Practitioners plan intentional, adult-led activities, and respond to child-initiated activities.

Curriculum is also associated with compulsory education, as a formal, planned programme of teaching and learning, and there have always been concerns about the ‘push-down’ effects into ECE.

Currently there are ongoing tensions between these two positions. In EYFS policy, the terms curriculum and educational programme are used, and incorporate the ELGs, in the Prime and Specific areas. The EYFS is outcomes-based, with assessment focusing on how those outcomes are achieved by individual children.

Bold Beginnings

In the Ofsted report Bold Beginnings: The Reception curriculum in a sample of good and outstanding primary schools (2017), there is much confusion and some contradictions.

One key finding of this report states, ‘There is no clear curriculum in Reception. Most leaders and staff in the schools visited acknowledged that there was little guidance about what four- and five-year-olds should be taught, beyond the content of the ELGs. They therefore determined their own curriculum, above and beyond the statements in the EYFSP, to prevent staff using the ELGs as their sole framework for teaching’.

This seems to imply some autonomy for teachers in their curriculum planning, but at the same time Bold Beginnings validates practices that focus on implementing and achieving the ELGs (with reading, writing and mathematics as priority areas). From the perspective of Ofsted, the curriculum is ‘what children are taught’, with the transition to ‘formal’ learning taking place during the Reception year.

The revised ELGs present closer alignment with the National Curriculum, and the increasing emphasis on school readiness reflects those ‘push-down’ effects.

A narrow understanding of curriculum

Based on these policy trends, I argue that alongside the EYFS, the direct intervention of Ofsted in matters of learning and teaching, play, assessment and school readiness constructs a narrow understanding of curriculum. Ofsted frames curriculum as ‘intent, implementation, impact’, which represents a linear and mechanistic approach to teaching as input and learning as output.

What and whose knowledge matters are presented in the ELGs as developmental lists, consisting mainly of skills and behaviours that practitioners can observe, assess and record. The goals are organised in a linear sequence, and the assumption is that all children can be judged on an individualistic basis against these norms, with some variations in the pace of development.

Although we can understand the EYFS as an attempt to secure an educational entitlement for all children, the ELGs reflect only minimum standards. There is little conceptual content in the goals on which to design a vibrant curriculum that is relevant to children in a diverse and changing society.

Framing curriculum as ‘intent, implementation, impact’ raises questions about equity and diversities, access and inclusion, so we should not understand the EYFS and ELGs as encompassing all that is desirable or possible for children.

Little space for flexible planning

When compared with frameworks in countries such as New Zealand, Norway, Denmark and Ireland, the EYFS is instrumental and arguably leaves little space for flexible, responsive planning, especially for children in the Reception year (ages four to five). However, it is important not to sustain opposition between play/work, formal/informal, structured/unstructured, prescribed/flexible approaches to the curriculum.

In flexible approaches, research indicates that practitioners may not consistently identify children’s interests and emergent knowledge, or use these effectively as the foundation for responsive curriculum planning.

In structured approaches, the focus on achieving defined learning outcomes through formal teaching leaves little space or time for practitioners to elicit children’s interests and emergent knowledge.

In both cases, it is easy to miss the important conceptual content of children’s thinking and learning, and how they might connect their ‘everyday knowledge’ and experiences with the ELGs.

When thinking critically and pragmatically about curriculum in policy-intensive ECE environments, practitioners have to find an appropriate blend of approaches, and create some in-between spaces and possibilities.

To find these spaces and possibilities, the question needs to be asked – whose and what knowledge matters? So, let’s move to reflecting on ‘knowledge’ and why it matters to children.

WHAT KNOWLEDGE IS AND WHY IT MATTERS IN YOUNG LIVES

A dictionary definition indicates that knowledge consists of facts, information and skills acquired through education or experience, and the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject (as in the typical curriculum subjects, or areas of learning in the EYFS). The word ‘acquired’ implies an input-output process, which is consistent with Ofsted’s model of ‘intent, implementation, impact’. In contrast, the term ‘emergent’ more accurately conveys the continuous and dynamic processes of learning and coming to know.

The concepts of emergence, co-construction and co-creation convey the multi-modal ways children and adults interact with each other, their relationships with the human/non-human and material worlds, and connections between everyday events and cultural practices in their homes and communities.

Within our complex and hyper-connected world, children use many different types of assistive and mainstream technologies and have access to thousands of apps and websites, media and popular culture. Knowledge is not fixed, but fluid and changing, so knowing how (for example, navigating digital resources) is as important as knowing that (for example, finding facts and information to develop understanding).

Ways of coming to know are embodied and distributed in relationship with people, materials and places. It is worth noting that learning and teaching in pre-school and home contexts share many similarities, including intentional teaching from family and kinship members (for example, telling, showing, questioning, wondering, explaining, imitating, repeating), as well as children’s own choices, explorations, questions and enquiries.

Building knowledge: a case study

These ideas are illustrated by an interaction between Sajid and his Reception teacher, Jenny: ‘I saw a big, big whale on Blue Planet[spreads arms and chest wide], with my dad. And the whale, he had this blowhole on his head [pats hand on top of his head] – and all the water went whoosh like this (throws arms up in the air). Is a blowhole same as a nose? Can the whale smell? Can fishes smell?’

Sajid’s embodied knowledge is shown by his physical actions and excitement about the shared activity at home. The teacher’s response was co-constructive – she asked open-ended questions about where they could find more information to answer his questions, helped Sajid with reading the text on the tablet, and encouraged him to use art materials to represent his thinking.

Jenny’s weekly practice was to note children’s questions and enquiries and share these during group time. Children were encouraged to talk about their processes of coming to know, thereby developing their metacognitive capabilities (thinking and talking about their learning, creating and solving problems, self-regulating), and sharing their knowledge and interests.

Children’s knowledge is often seen as being fragmented or naïve, and an ongoing challenge in ECE is understanding how children move from ‘everyday’ to ‘scientific’ knowledge (that is, represented in the subject disciplines). For instance, it is often claimed that sand and water play enable children to learn important scientific concepts – volume, capacity, density, measurement, properties of materials. But such learning does not happen in the absence of accurate language to explain concepts, and the ability to respond to children’s questions in intellectually honest ways. While processes of discovery and exploration are important, children need to know what they have discovered.

Learning in diverse ways

Young children encounter knowledge and ways of coming to know through experience in their homes and communities, in different social and cultural contexts. In addition, different forms of knowledge are valued (such as knowledge of cultural and religious practices, shared family stories and memories), all of which contribute to children’s identities and sense of belonging. Children’s learning is not necessarily fragmented, rather in the everyday world it is not as orderly or sequenced as child development theories lead us to understand.

And herein lie further problems when thinking and talking about curriculum in creative and critical ways. Understanding child development as linear stages and sequences, coupled with the narrow framing of the ELGs, serves to box in practitioners’ thinking, and certainly to box in children’s capabilities and potential.

In fact, child development theories have not kept up with contemporary social and cultural developments because children are doing so much more than has been thought possible, and are learning in many different ways in super-diverse communities.

In Nursery World (2018), I wrote an article with Aderonke Folorunsho and Liz Chesworth about young children learning with digital technologies (https://bit.ly/34Odcis). The article captured just a few examples of children’s interest, enthusiasm and engagement, and indicated how their learning is connected across digital and traditional play, how they make their own connections in collaboration with friends and families, and how they create their own play cultures and practices.

Knowledge is power in the sense that children revel in their new skills, capabilities and understanding, and enjoy putting them to work with creativity, invention and playfulness. Facts and information can be imbued with surprise and wonder, and new skills open up new possibilities. At the same time, children are constantly learning about themselves, their place in their social and material worlds, and the impact of their actions with and on other people and things.

Integrating pedagogical approaches

Let’s now come back to the concepts of emergence, co-construction and co-creation as counterpoints to ‘acquisition’. I argue that these concepts incorporate concerns with equity and inclusion, because they invite us to engage with children’s ways of coming to know, and with things that matter to them.

In the context of our super-diverse and fast-changing technological world, this understanding does not undervalue literacy, mathematics, sciences, technology, the humanities and the arts. The ‘subject areas’ are powerful and useful ways of organising knowledge and specific skills of enquiry, providing accurate explanations for children’s questions and, in the example of Sajid, knowing where to find out information, answers and facts that are of immediate significance and interest.

I am not presenting an outdated argument for a focus on processes rather than the structures and content of curriculum in ECE. Rather by looking creatively at the idea of in-between spaces and possibilities, we can understand curriculum as incorporating the dynamic, lived experiences of children, families and communities.

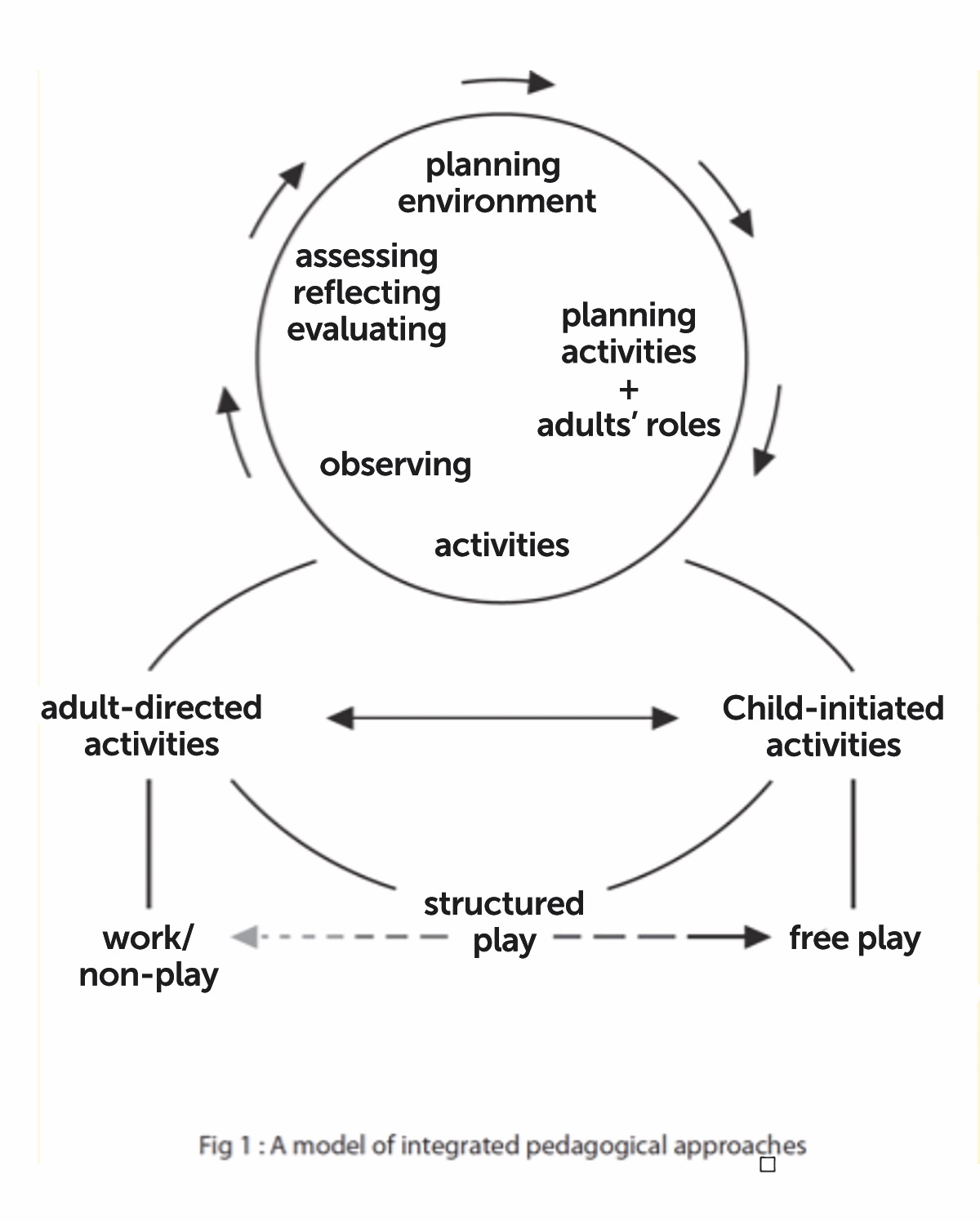

I developed the model of integrated pedagogical approaches as a pragmatic response to some of the questions and challenges that practitioners grapple with, especially in addressing some of the binaries noted above (play/work, etc. – see diagram).

The planning cycle is informed at each point by reflecting and evaluating, and allows for ongoing changes in practitioners’ responses to how children are using the environment, their different ways of engaging with activities, and the knowledge they bring to the setting.

As shown by the bi-directional arrows in the diagram, curriculum decision-making is dynamic and incorporates the principles shown in the text box. The key concept here is that curriculum planning can be intentional, responsive and anticipatory and moves flexibly to and fro across the continuum of adult-led and child-initiated activities. However, it is important to provide time for genuinely free play that is free from adults’ plans and purposes.

In this model, curriculum is much more than ‘intent, implementation, impact’ because it becomes the lived experiences of children, and incorporates knowledge, skills and understanding within their pre-schools, homes and communities as well as the ELGs. This is not just a ‘watching and waiting’ approach to see where children are engaged and involved, but focuses on the interests and enquiries arising from their activities.

If we accept that the EYFS provides a basic entitlement then we can use this model to be more creative in looking at multiple sources of curriculum content, including digital resources, and the social, material and affective qualities of learning.

Elizabeth Wood is professor of education at the University of Sheffield, and head of the School of Education. Her research interests include play and pedagogy and curriculum and assessment in early childhood education.

Summary: ‘knowledge’ in the early years curriculum

- An early years curriculum can arise from children’s choices, activities and experiences and build on the knowledge they bring from their homes and communities. Curriculum is also associated with a formal, planned programme of teaching and learning. There are tensions between these two approaches.

- The Early Learning Goals coupled with Ofsted’s intervention in assessment, school readiness and framing the curriculum as ‘intent, implementation and impact’ produce a linear and narrow understanding of curriculum.

- With both flexible and structured approaches to curriculum development, it is easy to miss the important conceptual content of children’s thinking and how it might connect to their ‘everyday knowledge’. Practitioners have, therefore, to find an appropriate blend of approaches.

- ‘Acquiring’ knowledge implies an input-output process. It is far more useful to view knowledge as emergent, co-constructed and co-created by children and adults in their homes, communities and settings, and incorporating intentional teaching as well as children’s own choices, explorations and enquiries.

- It is also important to note that knowledge is fluid and changing, so knowing ‘how’ is as important as knowing ‘that’. Child development theories have not kept up with the many ways in which children are now learning, including through digital technology.

- By integrating pedagogical approaches, practitioners can develop an approach to curriculum planning that moves flexibly across the continuum of adult-led and child-initiated activities and also incorporates genuinely free play.

- Most importantly, such an approach can incorporate children’s knowledge, skills and understanding within their pre-schools, homes and communities, as well as the ELGs. It can provide the conceptual content to design a vibrant curriculum that is relevant to children in a diverse and changing society. And it can address concerns about equity and inclusion, because it engages with children’s ways of coming to know, and with things that matter to them.

A MODEL OF INTEGRATED PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES

- Curriculum decision-making is dynamic

- Planning can be intentional, responsive and anticipatory

- Children’s interests are not just expressed as activity choices – they are content-rich

- Curriculum as lived experiences

- Continuum of activities to support responsive planning

- Activities can be led/structured by children and/or adults, but…

- Free play is for children’s meanings and purposes

- Allow time for using and applying skills, knowledge and concepts

- Tune into multimodalities and converged play

MORE INFORMATION

With thanks to practitioners and children at N London Fields, www.nfamilyclub.com/n-london-fields